CoDesign in Practice

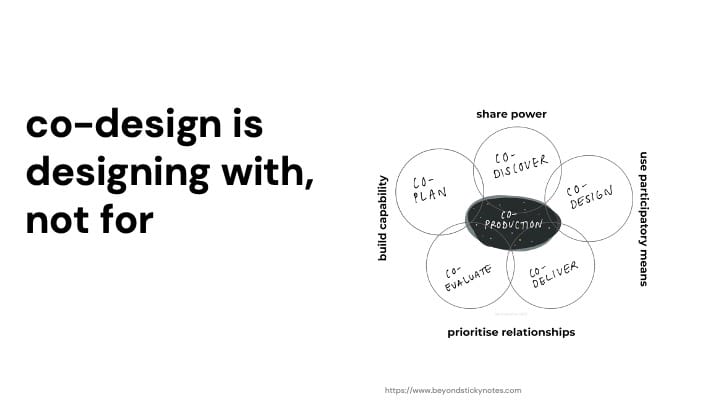

Designing With, Not For

“Co-design brings together lived experience, lived expertise and professional experience to learn from each other and make things better – by design.” – McKercher, K. A. (2020), Beyond sticky notes

Monisha: Gamar, the work you’ve done is really inspiring — especially the way you’ve worked with communities and emphasized the importance of building relationships. Now that you’re in a corporate setting, how do you see relationship-building happening, especially with all the time pressures and other constraints? And how do you think we can encourage people to approach problem-solving more collaboratively, rather than from a top-down, expert-only perspective?

Gamar: By nature, I’m a community builder. I build relationships quickly, and I’m really grateful for that. In community settings, it just comes naturally. I can show up as myself, share who I am, where I’m coming from, and why I’m there. There’s never a sense of, “I’m from an institution and you’re a community member.” That kind of barrier doesn’t exist for me.

But I’ve noticed that others, especially those coming from institutions, sometimes carry that barrier with them, whether it’s intentional or not. It might be part of how they were trained or just the culture they’re coming from. I try to break that down as much as I can.

In corporate environments, especially in digital product and service spaces, things are different. The way industries have evolved has created silos. People are so consumed by their own day-to-day responsibilities that it becomes really hard to reach across those divisions. So if you try to connect with someone outside their silo, they often just don’t have the time or the context for it.

That’s where intention really matters. It’s about how you reach out, how you introduce yourself, and what your purpose is. And you can’t do it alone. You have to start building allies within the organization or client team. It becomes a collective effort to engage others across silos. Sometimes that looks like hosting a meeting with a clear purpose, starting with proper introductions or even an icebreaker, and taking time to explain why you’re gathering and what you hope to achieve together.

Because if you just send an email saying, “Hey, we’re having a co-design workshop, your attendance is required,” that never works. People show up, but they’re completely disengaged. That’s why the co-planning and co-discovery process is so important. The more people are involved early on, the easier and more meaningful the rest of the process becomes.

Monisha: You’ve been fortunate to have the experience of working with communities and then moving to a corporate space. For students who are graduating, like me—I’m not sure if I’ll have the opportunity to work directly with organizations that work with communities. I might start my work in a corporate setting. As an educator, what are the tools or methods you use to help prepare students to apply what they’ve learned about co-design, no matter what kind of workspace they enter?

Gamar: One of the classes I teach [at Parsons School of Design] is Design Research Methods, and it’s a great entry point for introducing students to co-design. Co-design isn’t just a set of tools, it’s a mindset. So my focus is on helping students develop that mindset: being open to discovery, embracing different ways of doing things, truly listening to others, and learning to step outside of themselves to recognize their own positionality. There are ways to guide students into thinking that way.

From a methods perspective, systems mapping is one of the most powerful tools I teach, because co-design and systems thinking really go hand in hand. When you’re working with a community, you’re engaging with an entire ecosystem. And if you don’t understand that ecosystem, how can you co-design within it?

One of my favorite exercises is the implosion method by Donna Haraway. It starts with a single object and asks you to “implode” it—to explore its political, economic, cultural, educational, and symbolic dimensions. It’s about unpacking the world behind that object and surfacing all the systems connected to it.

That process helps students think more broadly and contextually so they can respond to what they’re seeing in a collective and intentional way. And of course, at the heart of all of this is openness and deep listening.

One of the hardest things to teach, honestly, is how to conduct an interview, just being present, really listening, and resisting the urge to jump in. Because it’s not about you, it’s about honoring the lived experiences of the person you’re speaking with.

So as a designer, as a facilitator, the real question becomes: how do you sit with discomfort? How do you hold space without always trying to fill it? There are many ways to teach that, but those are some of the approaches that come to mind for me.

Monisha: Those are helpful and practical suggestions for students—both in our professional and personal lives. You use a lot of visual aids like sketches, diagrams, and sticky notes to facilitate and co-produce sessions with communities. It actually reminded me of McLuhan’s The Medium is the Message. I really believe that the tools you use are just as important as the intent behind the process. Did you ever develop any tools onsite with people that were contextually relevant or drawn from their own lives?

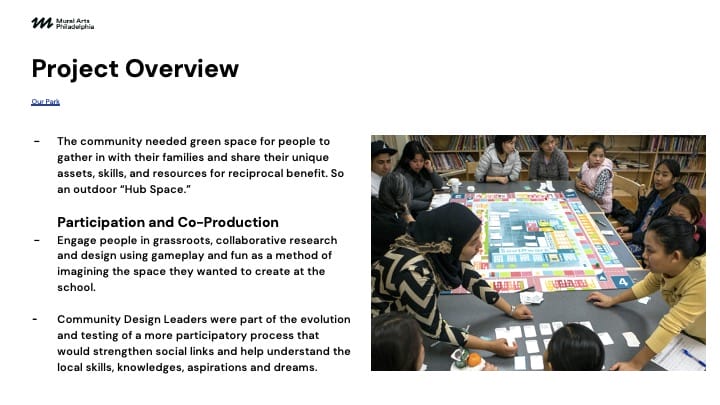

Gamar: Oh yes, absolutely. The game itself followed a format similar to Cards Against Humanity, where players respond to fill-in-the-blank statements. The stories behind those statements came directly from knowledge-sharing sessions we had with the community and they were drawn from what people shared with us.

The school district invited us to work on more projects afterward because this one was seen as such a success. So I carried a lot of lessons from that process into other schools.

But if I could go back, one thing I wish we had done differently was to actually co-design the game itself with the community. Mateo Fernández-Muro and I created it using the insights we had gathered, but I wish we had tested it more with the people we made it for, gotten feedback, identified gaps, and maybe even added new themes based on what was important to them.

So while the content of the participatory method came from the community, the structure of the method was something we built. That was the case with other tools, too—like the mapping activity. Even though mapping is a common method, we grounded it in the book Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino.

For Postcards from the Future, for example, I created an illustration imagining what the schoolyard could look like in the future. From there, we asked people to imagine their future selves writing to their current selves. All of those ideas eventually fed into the game Mateo and I designed.

What I love about co-design is that it asks you to be really comfortable with ambiguity. There’s no universal method—it’s all about adapting to the context, to the people, to the moment. When the conditions are right, things tend to fall into place like puzzle pieces.

It might sound abstract, but I really believe this: if you want to practice co-design in any space, you have to be okay with not having everything figured out. You don’t need a minute-by-minute plan. You just need to be present, responsive, and open.

Monisha: We’re often reminded to embrace chaos and discomfort in school too. What recommendation do you have for students or new graduates who want to go into community engagement and design and get hired by a firm that claims to do that, but is very closed off in their way of working?

Gamar: The truth is, trying to fight against the institutional structure of a company usually doesn’t work. So my number one piece of advice? Focus on building relationships within the organization.Start conversations about what co-design actually means even if it takes time. Education is a big part of this work. People need to understand the practice, and they need to believe in it. They need to buy into the idea that true collaborative design leads to better outcomes, not just in theory, but in real, practical terms.

I’ve worked in urban design contexts where engagement was treated like a checkbox: “Yeah, we talked to people. We held one meeting. Got some feedback.” That’s not co-design—that’s performative. In an earlier conversation with you, I brought up Arnstein’s Ladder of Participation. It’s a really useful framework. Sometimes I’ll literally pull it up and say, “Look, what you’re doing falls under tokenism.” If we’re aiming for real participation and building trust with the people we’re designing for, then we have to move up that ladder toward real partnership and, ideally, citizen control. That’s the top of the ladder, and I’ll be honest—it’s incredibly hard to get there. But you can start small.

Maybe next time, ask for a few extra weeks in the project timeline. Set aside a budget to compensate community members for their time and expertise. Even those small steps start to change the culture around how we work. It’s really an ongoing conversation—an educational process—with the people inside the organization. You’re not going to change minds overnight. It takes consistency, storytelling, and a lot of relationship-building. Bring in examples of where co-design has worked, even if it’s from student projects or experiences outside your direct work. If it’s real and relatable, it can help make the case.

I was lucky when I started this work after my master’s as I didn’t face a lot of pushback. But in many places, you’ll need to earn people’s trust first. Keep showing up, keep having the conversations, and look for ways to move the practice forward one step at a time.

Monisha: You mentioned relationship-building as a core part of your work. What do you believe are few other non-negotiables of co-design—no matter the context?

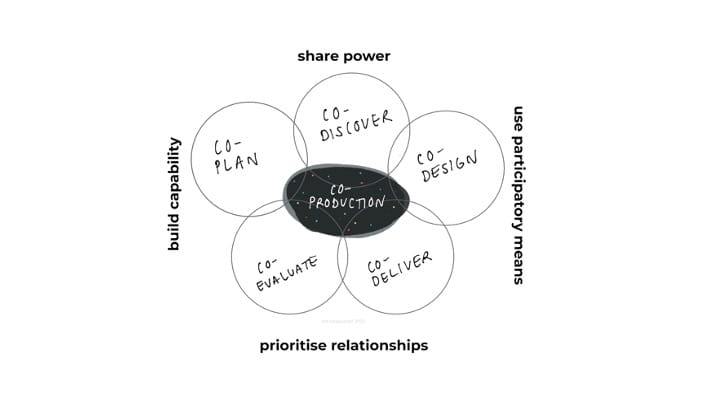

Gamar: Relationship-building, or as I like to call it “Making Friends,” is definitely at the heart of it, but there are a few other things I think are non-negotiable in co-design, no matter where you’re working. One is a real commitment to sharing power. That means bringing people in from the very beginning—not just to give input but to co-discover, co-plan, and co-deliver. It’s about creating space for people to genuinely shape the work with you.

Another big one is being okay with ambiguity. Co-design isn’t clean or linear—it’s messy and unpredictable, and that’s part of the beauty. You have to be open to where the process takes you, to listening deeply, and to shifting plans as things unfold. That flexibility is what makes it possible to really respond to what people need.

And context is everything. You can’t apply a cookie-cutter approach. Whether you’re in a community setting or inside a big organization, you have to be aware of the dynamics, power structures, and lived experiences in that space. Honoring context is what builds trust—and trust is what makes the work meaningful.

Monisha: Since co-design requires a tailored approach in every context, do you think this constant need for adaptation can become exhausting?

Gamar: Honestly, I wouldn’t say it’s exhausting. Sure it takes energy and time, especially if you’re always the one holding space for others while also navigating shifting dynamics, expectations, and constraints. But I think adaptation is necessary, and it should be honored as such. Co-design asks us to stay open, to keep tuning in, adjusting, responding, and that’s what makes it powerful. But I think that’s where the need for reflection and support systems becomes so important. The constant adaptation isn’t just about being flexible but it’s about being responsive with care.

Over time, you start to build up some muscle for it. You pick up patterns, tools, ways of doing things that you can carry from one project or space to the next. So even though every situation is different, you’re not starting from scratch each time. And when the work is shared, and when there’s space for care in the process, it feels a lot more sustainable.

Monisha: How can designers and community-centered practitioners celebrate shared knowledge without being extractive?

Gamar: Celebrating shared knowledge without being extractive means recognizing that knowledge is never neutral, it’s shaped by lived experience, by power, by place. And when that knowledge comes from communities, especially those who have been historically marginalized or overlooked, it has to be handled with care and respect.

At its core, it’s about sharing power—not just inviting people to speak, but making sure those who hold the knowledge are shaping decisions and are acknowledged and celebrated as they do so. It means the process is guided by those closest to the realities being explored, not just interpreted by those facilitating the work (such as myself).

It requires us to ask: Who benefits? Who decides? And what does meaningful participation look like here? Avoiding extractivism means making sure that the knowledge shared isn’t separated from the people and contexts it comes from. So we need to be vocal about that. When we treat knowledge with reciprocity, clarity, and accountability, we move from “using it” to building with it, as a living thing that grows and evolves communally.