Interview with Dewayne Dale Jr.

Dewayne Dale Jr., originally from Shiprock, New Mexico, talks to Journee Harris about how his love for sports and shoes growing up in the Navajo Nation inspired his journey to become an industrial and footwear designer.

Listen to the full interview

Dewayne Dale Jr. Interview Transcription

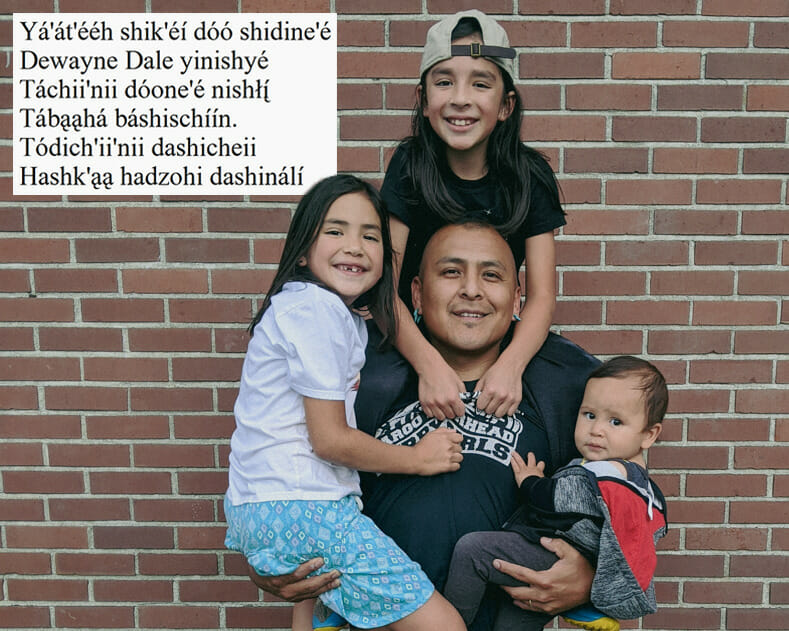

Dewayne: I’ll introduce myself in Navajo because it’s customary, so I’ll start with that and introduce myself in English after.

Hello my relatives and my people.

My name is Dewayne Dale.

I am of the Red Running into the water clan.

I am born for the Water’s Edge clan.

The Bitter Water Clan are my maternal grandfathers.

The Yucca Fruit strung out in a line clan are my paternal grandfathers.

Usually, for anybody who’s listening, who is Navajo, it’s a cool way to see how we’re related. So, that’s why you state your clan and state at the beginning of any introduction or if you’re speaking to anybody in a group. But, yeah, Dewayne Dale, from Shiprock, New Mexico, which is on the Northwestern corner, Northern part of the Navajo Nation. And my role is an industrial designer and footwear designer. Happy to be here talking with you.

Journee: Tell me about where and how you grew up.

Dewayne: So, it was on the Navajo Nation, which is a Navajo reservation. Growing up, you don’t realize that the word reservation doesn’t have the same meaning as you get older, like when you start to realize how reservations were formed. But at elementary age, you don’t really realize that you’re doing things differently than people outside of your community.

I was heavily involved in sports, and most of the teams I played against came from non-native schools. Once you start to drive back and forth over the reservation borders, it begins to hit you, you’re living in this place that’s not a different state. It’s not a different county. It’s like you’re crossing over this invisible line that separates you. So growing up in that way, I felt like I was living in these two worlds, so to speak, I have the world of Navajo culture and traditions and then everything else outside of it. I always felt like I was kind of in the middle, trying to survive and adapt to both sides because they were different.

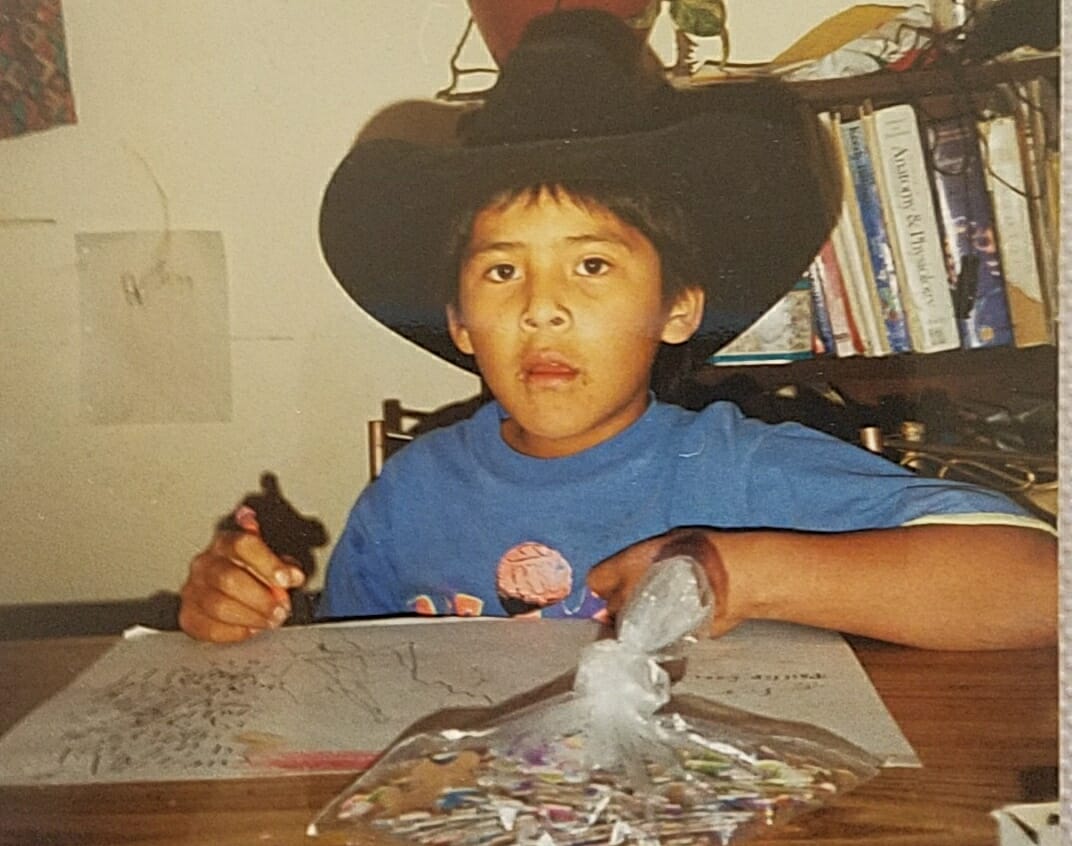

Dewayne as a child.

I grew up in a rural area. It was high desert, the Southwestern area of the United States. We moved around when I was younger, but one of my bigger memories was growing up on a farm. The farm was maybe two to four acres. Still, we grew everything from alfalfa to corn, squash, watermelon, and everything was planted by hand. That was some of the ways we, my parents and my grandparents, raised money each year.

I feel like it’s really hard to explain outside of just growing up on a reservation. There are limits to a lot of things in terms of resources, like water or housing was always a big thing. So there’s always a blend of many limitations, but then there’s freedom. There’s hardly anybody around. You can go where you want to go. If you drive five minutes outside of your town, you feel like you’re in the middle of nowhere. You’re smack dab in the middle of a desert with mesa plateaus and all these kinds of cool surroundings. When I’m talking to a local or a friend about growing up on a reservation, we don’t have to explain it. There’s a mutual understanding of the lifestyle and environment. It feels slower at times, which is nice, but also so slow to where you’re, you’re just not up to speed, like when I was living in Portland. Things are happening so fast in Portland, Oregon and that’s just the total opposite from back home.

The Navajo Nation is huge. If you were to drive east and west of the Navajo Nation, that’s a solid four hours, and then north and south might be like three hours. So it’s a big chunk of land. And on that land, there’s a lot of small communities, some bigger communities; all usually have only one grocery store. So most of the time, you’re heading out to get stuff and bringing it in. In some parts, there are a lot of free-roaming cows and horses and stuff that are out grazing. It sounds liberating to a lot of people. Still, sometimes I feel like there are limitations. Just thinking about how I grew up and can do what I’m doing now. I always go back and think, man, if more of this stuff was taught to, or if more of the kids growing up in the Navajo Nation can see what’s happening, it’s almost like, their world would just grow bigger.

Growing up, I feel like I learned to adapt a lot. Adaptation is a huge theme that I carried with me through college and even until now. It’s a constant. You’re always adapting. Whether it’s the design space, the workspace, or the company you work for. Adapting was a tool that I wanted to keep, and now it is one of my biggest strengths.

Journee: What were your interests as a kid? What were you exposed to that has influenced your work today?

Dewayne: This takes me back to growing up on the farm. We didn’t have electricity and I think we had water through a well system. The water would be turned on by my dad outside, and then we’d take a bath and do all the normal stuff, but then it had to be shut off. You couldn’t turn the tap on and water would come out. In third, fourth grade, I remember still using oil lamps for homework and stuff. I had to get stuff done early and then do chores if my mom and dad asked, but just being outside and kind of being this, dirty kid <laugh>. I feel like that was when I became fascinated with how things work. Whatever we had, I took it apart.

I was doing a lot of drawing and at one point didn’t realize that the skill of drawing would help me when I grew up. To me, people who drew were artists who drew these really cool pictures that usually hung in a museum or something like that. I never realized that the artist or the artistry part of sketching and doodling has a place in the design world. Drawing is a valuable and useful language to get what’s in your head out so people can see it.

Growing up, I feel like I learned to adapt a lot. Adaptation is a huge theme that I carried with me through college and even until now. It’s a constant. You’re always adapting. Whether it’s the design space, the workspace, or the company you work for. Adapting was a tool that I wanted to keep, and now it is one of my biggest strengths.

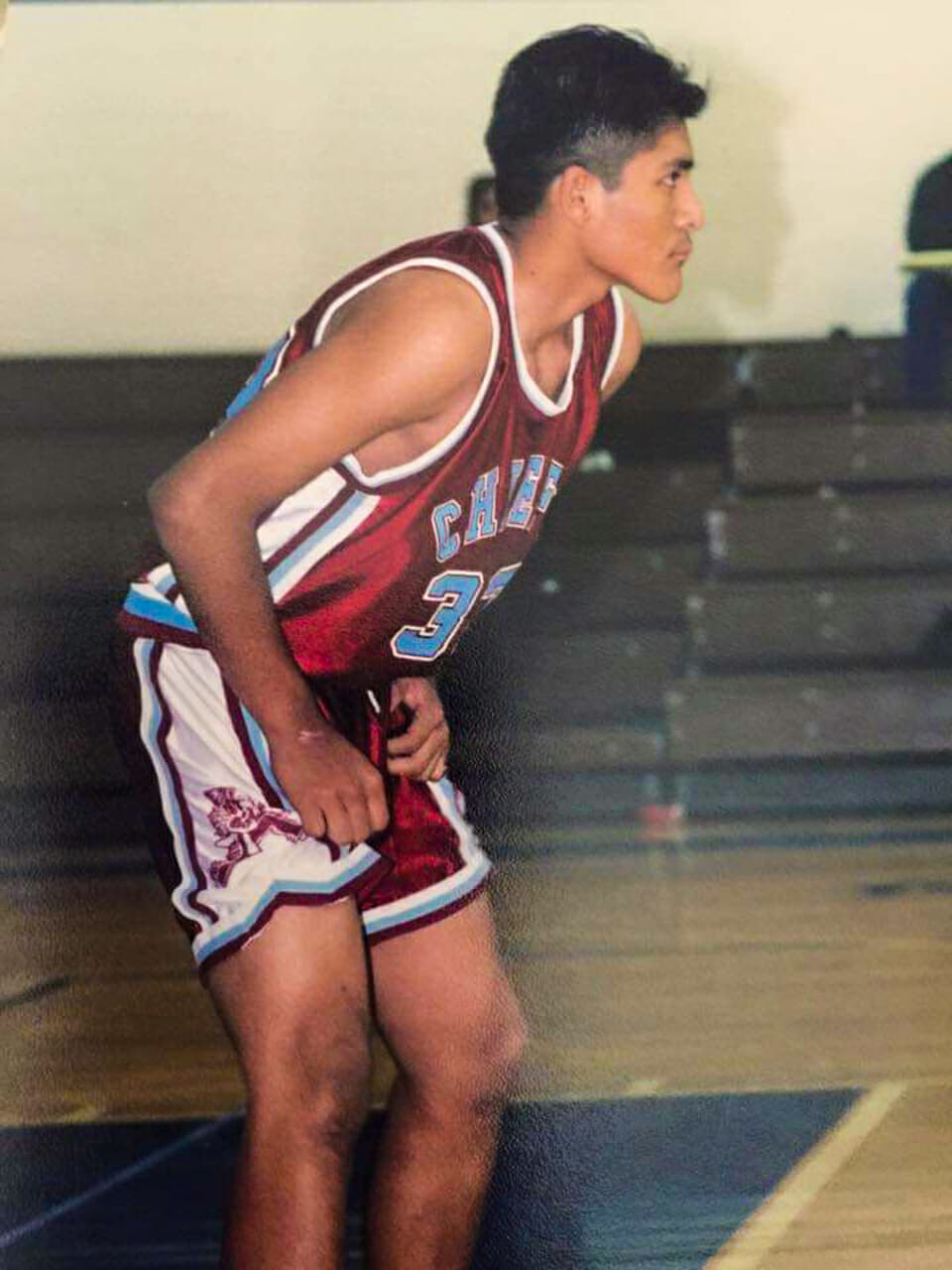

Dewayne playing basketball.

Journee: Tell me about when you left the reservation.

Dewayne: When I first left for a long period of time was for college, but before then, being involved in sports allowed me to travel. I grew up playing baseball, basketball, and football. When I first left the reservation, it was for college. I got the opportunity to play baseball in North Dakota. When that opportunity arose, I didn’t want to turn it down because back then, there weren’t many people who left to play college sports, let alone have that sport pay for your college.

I graduated high school in 2003 and went to undergrad, played baseball, and I loved science. I loved medicine. I wanted to go into sports medicine and be involved with athletes because that’s the world I grew up in, and I thought it would be awesome to remain in that field. I attend a small college in a smaller college town, but for me, that was perfect. Being away from home is tough for any college kid. Still, I think it is more tough for some minorities because you literally get dropped in a place where nobody looks like you. That was the case for me when I went to college. I realized that I was the only person like me in every single class. So, I adapted and accepted that was just kind of how it was and kept moving forward, which was an interesting way of thinking. My next college was North Dakota State University in Fargo, North Dakota. That was where I did my graduate work. After that, I went to school again for industrial design at the Art Institute of Portland in Oregon.

Journee: Did your family or your community have any type of conversation with you before you left for college, preparing you for being around so many people who weren’t like you?

Dewayne: No. The way I was brought up was, you just treat people like you want to be treated. But we never really had those kinds of conversations. For me, it was more joking about being the only dude from Navajo Nation in that college town, which was true.

Journee: What was the most difficult part of transitioning, I’d say academically, from sports medicine to industrial design classes?

Dewayne: The biggest thing is that you’re really not taught to think in a very linear path when you go into anything like art or design. I’m not trying to reduce swelling in a twisted ankle, right? With design, I can’t follow steps. There’s not a recipe and then a result. It’s more that you really gotta put yourself in someone else’s shoes every single time. If I’m gonna design something for a tennis player, I want to know what they do. I wanna know what their life is. I wanna know what their workouts are like, so for me, the biggest difference is empathy, what and who is this person? You kind of gotta play a detective. How can you become this person and feel what this person’s like to create this product for them? That’s the part I’ve always liked about switching over because then that opens up my world. And then every concept becomes an answer to this small problem. Whereas going back to what I was talking about, there’s a protocol to a twisted ankle, you ice, you exercise, then ice again.

Journee: Going into the work that you do now. Your website and Instagram lists you as an indigenous designer, and it might seem really obvious, but I would love for you to talk about how you created that name and what branding yourself and your skillset in the design world has been like.

Dewayne: I’m glad you asked that question. Not many people asked that because indigenous designer just sounds like a description, which it is. Still, it all started back when I was finishing up my third industrial design program. Again, I was the only Navajo person in the program so I wanted it to have this play on words about me being an indigenous person, but at the same time, I always felt like design was very much me from the beginning and in that way indigenous designer means two different things.

When I started to vectorize my face, at first, it was a joke, like getting a tattoo of your own face. But I felt like there weren’t many people like me in Portland, and I just needed to do something with the way I looked. I wanted to put a face, a figure, an image so people might think, “this person might be indigenous.” I don’t like when companies, or anybody, generalize what native people look like. My work takes a little more of a modern approach that’s less in your face. But when you look at my stuff, maybe I did some things tied into deeper stories of native people.

Journee: You personalize it where it’s not just like someone would see your design or see your logo and be like, “okay, a native person,” they’d be like, “oh, Dwayne.”

Dewayne: Right, yeah. When you open up my website, you’re not gonna see tribal print. I was heavily involved in innovation thinking when I worked on design teams. I loved that because I worked with awesome people who understood the value and importance of having people of different ages, races, backgrounds, and all walks of life come together to work on a project. And that, in itself, creates an innovative process. I look at things differently because of how I grew up. I look at how you did homework at night versus how I did homework at night. There’s just these different things that lead people in different directions, which is what I loved about being in that innovative space. And the solution is always so cool. That’s one of the fun things I like about design and creating something that no one’s seen.

Journee: Speaking of that, can you talk about the Fifth x Rockdeep M.1 Trail sneaker?

Dewayne: That collaboration between myself and Rockdeep started back in June/July of 2020. Rocky Parrish who’s the CEO of Rockdeep, reached out and pitched an idea. We talked and I told him that I had wanted to do a collaboration like this for a long time and I already had the design. I’ve always wanted to design based on history and on early footwear. I’ve seen other companies do it and the shoes looked cool, but why do they look cool? I always knew why–it looked cool because it came from these early cultures. I don’t have the desire to go out and buy a moccasin sneaker because I don’t think there are any native designers pushing that envelope for those companies. I wanted to flip the script. I wanted to be behind the scenes controlling and curating all of that. So, Rocky left the design direction totally up to me and I was very appreciative of him putting that faith in me. I wanted to launch something that wasn’t just taking from a culture. I’m not gonna copy what a moccasin looks like but I want to take elements and celebrate them. The M.1 sneaker has a unique lacing system. When you look at moccasins early on, they were just looking for ways to keep them on your feet. So it would be wrapped in a certain way. If you approach a product like that, I think it’s cool because then you can visually draw someone in and they’re like, “wow, this is really crazy. You don’t normally lace up a sneaker like this.” Also, it stays on your feet. That’s my job is to not just make it look crazy and cool, but I want it to stay on your feet. So there’s all these things that designers think about.

My end consumer was my family. When I say family, it’s like all my relatives, all my other native brothers and sisters across the US into Canada and Mexico, all the indigenous people. They have a culture rich in footwear. People never really say, “oh, you know, you guys have this cool footwear. We wanna bring you guys in to make it.” No, they’ll take the picture and put it on an inspiration board and they’ll go that way without even acknowledging where it’s from.

Growing up in a place full of culture, I didn’t need to travel. I didn’t need to get inspired by Japan’s culture, Paris, or anything like that. I just need to go back and remember what was fueling my drive to design footwear. And for me, it was early footwear. It was moccasins. Not to take away from the people making them by hand, I felt like that was a product that could be elevated with modern techniques. I want something that has a stronger story.

I wanted to solve this question of why do I desire it? Why do people desire it? Once I answered that question for myself, then it became this need. Like, people need this, people need this the way they think they need another Air Force 1, or another colorway of Jordan 5. Once I answered why they wanted it, I felt like I could touch their hearts with this product. I can make them feel joy because they know the story and who is behind it. They know everything from sketching to talking with the factory. They know that there was no in-between person, it was just Rocky and I.

Journee: You were talking about this before, having empathy for the consumer and then the consumer also having empathy for the designer. It’s almost like you have a relationship with the people that wear and purchase your shoes.

Dewayne: Right. I think about 800 people bought the M.1. So it’s like having 800-plus relationships, and they all understand what I’m trying to do. So now, I want to create that experience when you first open it, when you put it on, when you touch it, there are all of these cool elements that I feel like I can affect if I’m really allowed to just express myself in that way.

Journee: My final question to you was, what is your favorite shoe or a shoe that kind of changed your life?

Dewayne: My favorite shoe is the Nike Air Max Uptempo 95. I can remember the day that I saw them in Foot Locker. It was the first time that Nike was really putting huge air bubbles around the whole thing. I love simple upper patterns. So when Nike was in that phase of simple uppers and textures, that’s kind of what got me. Yeah, it would be the 1995 Air Max Uptempo. It’s all white, black, like this black suede Rand with these visible air bubbles that were like teal on the bottom. That’s what got me, it was that colorway.

Dewayne and his partner wearing Air Max 90s at their wedding.

Journee Harris

Urbanist, Researcher & Storyteller

About the Interviewer

Journee Harris is a Storyteller, Urbanist, and Community Development professional based in Cambridge, MA. She is a first-year Master in City Planning student at MIT and a proud alumna of Howard University, where she earned her Bachelor’s degree in Psychology. Journee has worked in the non-profit sector, focusing on public space, housing, youth development, historic preservation, and equity in the built environment for over seven years.