Saving Future

A photo essay on our connection to the wild

Photos by Ami Vitale

By Ami Vitale, National Geographic Photographer and filmmaker

These giants we share this planet with are part of a complex world created over millions of years and their survival is intertwined with our own. Without them, we suffer more than a loss of a species. We suffer a loss of our imagination, a loss of wonder, a loss of beautiful possibilities. When we see ourselves as part of nature, we understand that saving nature is really about saving ourselves.

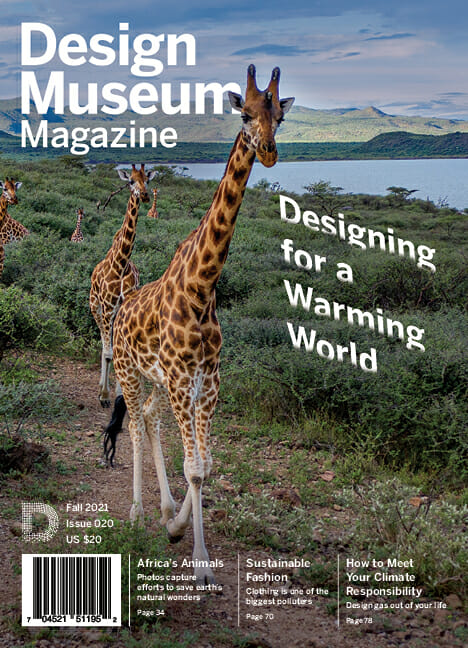

Daring Giraffe Rescue

A group of Rothschild’s (Nubian) giraffe were marooned on Longicharo Island, a rocky lava pinnacle in the middle of western Kenya’s Lake Baringo. The rising lake levels turned the peninsula into an island, trapping the giraffes. In a dramatic rescue, two were transported across the lake on a makeshift raft, to Ruko Community Conservancy.

Today fewer than 3,000 Rothschild’s giraffes are left in Africa, with about 800 in Kenya. “The hope is that this is just the first step of reintroducing these giraffes back to their historical home across the Western Rift Valley, hopefully over the next 20-30 years,” explained David O’Connor, president of Save Giraffes Now who helped orchestrate this inspiring move with the Northern Rangelands Trust and Kenya Wildlife Service.

Reteti Elephant Sanctuary

Reteti Elephant Sactuary, located in Northern Kenya, is the first community-owned elephant and rhino sanctuary in East Africa operated by the indigenous Samburu community. The sanctuary provides a safe place for injured elephants and rhinos to heal and a home for orphaned elephants and rhinos affected by poaching and the ivory trade. The communities living side by side to the wildlife hold the keys to saving what is left.

The Last Goodbye

The image below is of Joseph Wachira saying goodbye to Sudan, the last male northern white rhino on the planet, at Ol Pejeta Conservancy. I saw Sudan for the first time in 2009 at the Dvůr Králové Zoo in Czechia (the Czech Republic). I can recall the exact moment. Surrounded by snow in his brick and iron enclosure, Sudan was being crate trained—learning to walk into the giant box that would carry him almost 4,000 miles south to Kenya. He moved slowly, cautiously. He took time to sniff the snow. He was gentle, hulking, otherworldly. I knew I was in the presence of an ancient being, millions of years in the making (fossil records suggest that the lineage is over 50 million years old), whose kind had roamed around much of our world.

At 45, Sudan was elderly for his species. He had lived a long life, but now he was dying. In his last years he experienced again his native grasslands, although always in the company of armed guards to keep him safe from poachers. And he had found stardom—he’d been affectionately dubbed the “most eligible bachelor in the world.”

Sudan’s death was not unexpected, yet it resonated with so many. When I arrived, he was surrounded by the people who had loved him and protected him. Joseph Wachira, the man pictured with Sudan in the photo below and one of his dedicated keepers, went to give him one more rub behind his ear. Sudan leaned his heavy head into Wachira’s. I took a photo of two old friends together for the last time.

See more of Ami’s work here.