Interview with Candy Chang

Candy Chang is an artist pushing the boundaries of ritual in public life. She creates speculative rituals that speak to the pains of our age. Her public and interactive artworks invite viewers to question and discover how we use public spaces. Candy discusses her art practice and how it is informed by her work as a designer and urban planner in an exclusive interview with CoDesign Collaborative.

Candy Chang Interview

Where did you grow up?

My parents immigrated from Taiwan to the U.S., and I was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. As a little kid, I grew up surrounded by cornfields in Lima, Ohio.

When did you first start making art, and how was your creativity nurtured through your adolescence?

From my earliest memories, my sister was considered the bookworm, and I was the artist. I always liked to make things — comics, pretend radio shows, paintings, and illustrated crime stories — and my parents were amused as long as I got good grades. My mom thought I might die young because I was always sick, so she signed my sister and me up for any class she heard about to give us “all of the experiences.” I learned how to tap dance, oil paint, and barrel race on a horse. She made me braver to try new things.

What did you want to be when you were a kid?

I wanted to be an artist, which worried my parents, understandably. They imagined a life of pain and poverty and encouraged me to be a little more practical. I remember feeling jealous of people who seemed certain about their careers at an early age. I loved being creative, but that energy went in a dozen directions. I ended up trying a lot of things in different disciplines, and when I look back, I’m glad I did. The mashup of those experiences ultimately led me to make art in ways I could never have imagined before.

Candy Chang as a child.

You’re trained in architecture, graphic design, and urban planning, and the work you do today is unique and deeply sentimental. Walk me through the journey of your formal education and how it led to your current art practice.

I loved architecture, but I didn’t want to wait until I was an old lady to design something. That’s when I first heard of graphic design, and it was empowering — I could make my own experiments and websites. So after college, my friends and I started a design firm and record label. We made minimal techno and wheatpasted posters of our records around downtown New York, which got me into street art. It set off the mischievous side in me, and I had fun imagining all the things I wish existed in my neighborhood. That made me more curious about how the city works, and when I couldn’t figure it out on my own, I went to school for urban planning.

As I made money through design, I sought out grants and opportunities to do civic experiments with communities worldwide. I thought it was weird that we had more and more tools to reach out across the planet, but it was still hard to reach out to your entire neighborhood. And I had so many questions for my neighbors that I was too shy to ask in person. If our public spaces were designed differently, could we share more, learn more, self organize more? Street art taught me to be scrappy and do what I can with what I have, so I used simple tools like stencils, stickers, and chalkboards to make participatory prompts in public. They were like remixes of street art and urban planning to see what might happen if we could share more with our community.

My experiments took a turn when a close friend and mentor died. I became depressed, numb, and increasingly cynical. Everything in public life felt absurd. My inner world didn’t feel like it belonged outside at all. I spent a year spiraling towards self-destruction, but there was this abandoned house by my home in New Orleans that looked even sadder than me. It finally crossed my mind that it would break Joan’s heart if she knew her death made me give up. I wondered if I could do something to honor her and reflect on mortality. That’s when I asked a more personal question in public and made Before I Die on that abandoned house.

Above: Before I Die in Santiago Chile photo by Bernd Biedermann

Below: Candy Chang installing a Before I Die wall, photo by Kristina Kassem

The Before I Die wall grew in ways I never expected. I saw a wider range of humanity out in the open. I saw humor and joy mashed up next to pain and redemption. I saw heartbreaking things you don’t typically tell a stranger, like Before I die I want to… get through the grief of my divorce, overcome addiction, forgive and be forgiven, and bring peace of mind to my mom. People’s reflections made me feel profoundly less alone, and they gave me the courage to face my own struggles. I saw my neighbors in a new light, and it made me think about the value of anonymity to be more honest and vulnerable without fear of judgment.

Since then, I’ve become passionate about creating more infrastructure for the soul — to reflect, to forgive, to atone, and to see ourselves in each other. Over the last decade, I’ve made public rituals on loss, anxiety, and the darker corners of the mind, and I’ve seen just how much we’re all walking wounded. When we talk about healthy communities, we often neglect our psyches. Loneliness, stress, and anxiety have all been called public health epidemics. Those feelings can easily grow into addiction, depression, or self-destruction if we ignore them. At the same time, there’s a war on our attention, and we’re bombarded with distractions that feed some of our worst impulses. As the world feels more uncertain and alienating, there’s a lot of space to reimagine how our communities can better serve our psychological health.

For your project Before I Die, the walls aren’t just set up in one location, but they’re set up all over the world. What was your thought process for choosing where to set up those walls?

I’ve never chosen a place besides the first one. Since then, every Before I Die wall was initiated by passionate people who wanted to make a wall in their own community. I’ve had very meaningful experiences helping people make walls everywhere from Kazakhstan to Brazil, but I knew pretty quickly that I couldn’t keep up with the requests and that it only takes a few simple tools for anyone to make one. So I tried to make this project as open-source as possible by creating a website with some tools and tips for people to run with it in their own ways. Thanks to them, over 5,000 Before I Die walls have been created in over 75 countries! I feel like it’s everyone’s project now, and it grew despite my quiet ways. I’m very grateful and inspired by everyone’s walls, and it shows how much we want to create more spaces to restore perspective with our others.

I now have over a million handwritten reflections from people around the world, and I want to be a good steward of them. They feel like a more honest portrait of our society today and where we need help. They make me braver in my own self-examination and relationships. They teach me what helps us hold on and persevere.

Candy Chang working in her studio in 2021, photo by James Reeves.

How does your identity of being Taiwanese-American contribute to your work?

My elders adapted to a lot of authoritarian forces over their lives, and they taught me to never take democracy for granted. It compels me to question in ways they couldn’t and to be punk in a Taoist way. I’m also deeply influenced by the traditional Asian arts. Whenever I feel stressed, I look at Chinese landscape paintings where people are tiny in relation to the greater world, and it immediately knocks me out of my myopic thinking and puts my worries in perspective. I use an inkstick and inkstone, which are considered two of the Four Treasures of the Study. The process of physically grinding the ink and exploring all of its qualities has become a ritualistic exercise and a lesson in the multitudes from one humble ingredient. It inspired the artwork I made for Light the Barricades.

Maybe most of all, Chinese calligraphy inspired my love for the handwritten word. I grew up surrounded by scrolls of calligraphy that my dad thoughtfully curated on our walls, and my uncle took me to an outdoor art market in Taipei to have his favorite melancholy poem written out for me. There’s a reverence for meaningful sentiments written by hand, and I carry that through my participatory installations. Today many people say their handwriting is a wreck, but I love those idiosyncrasies because they evoke so much soul. My most cherished possessions are the handwritten notes from my family and friends. I’m now experimenting with the techniques of Chinese seals and ink rubbings to reproduce select responses on canvas.

Light the Barricades Doubt, photo by James Reeves

What are your current professional and personal goals?

I’m interested in the future of ritual in public life: speculative rituals that speak to the pains of our age, and I’m working on new public artworks that push the possibilities. I’m also interested in developing more personal rituals. The human psyche is both awe-inspiring and a tragic comedy. I know I’m not always my brightest self, so I think about how I can develop rituals to leave clear instructions when I’ve lost the plot.

During the pandemic, I spent a lot of time with reflections from past projects that resonated with me in the moment: I’m scared and exhausted. Our country is on the edge of disaster. The ability to find peace within chaos. It’s not over, and it really isn’t too late. I am still here. I carved, splashed, painted, waxed, and rubbed them like fleshy koans until my corner of the room started to look unhinged. But I eventually arrived at something that excited me and calmed me. It’s leading to a new body of work and meaningful rituals in my life.

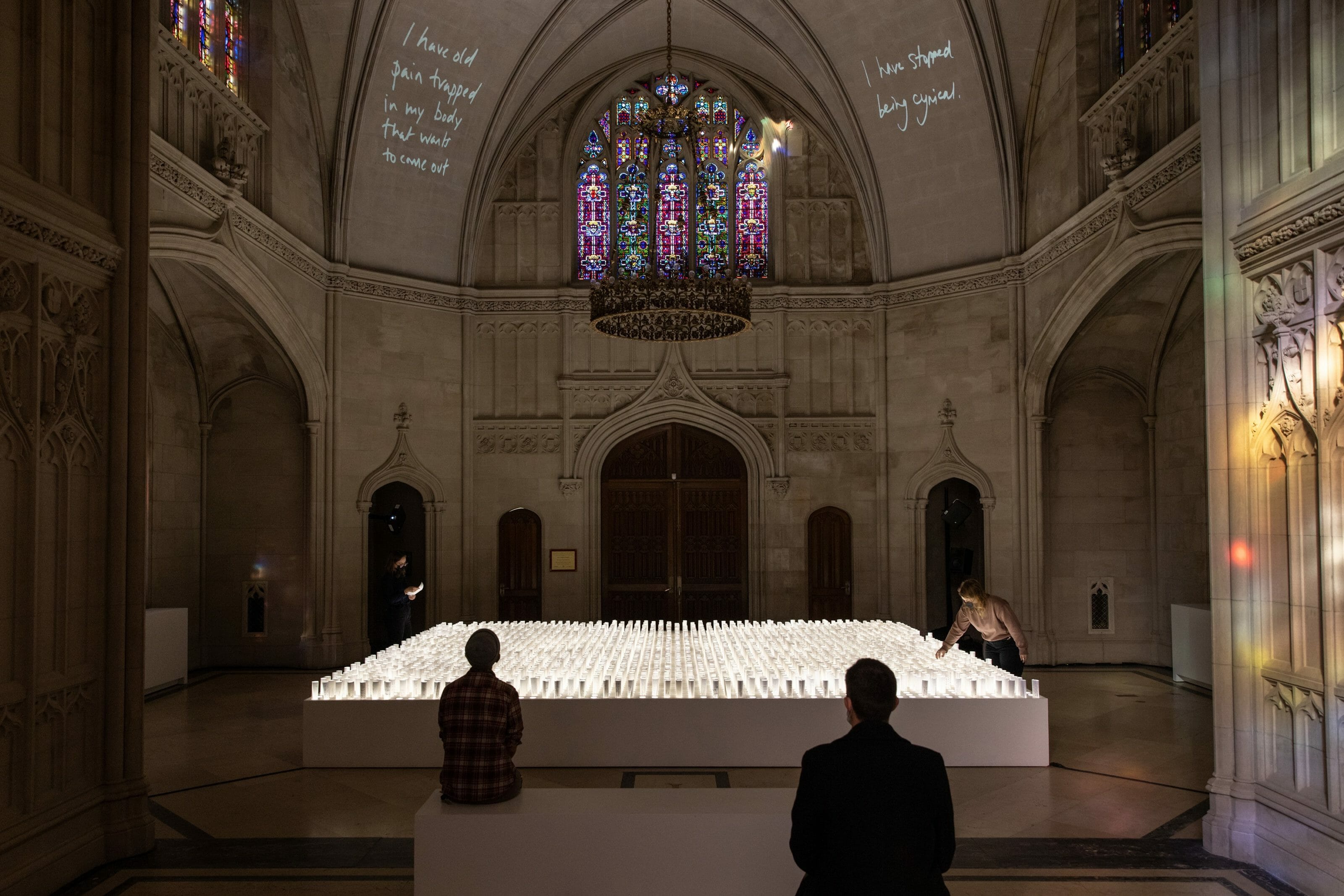

“After the End,” by Candy Chang & James A Reeves, photo by Walter Wlodarczyk

When do you feel most proud of yourself?

I feel proud when I pay attention to how I’ve grown. That’s the only important comparison, and it’s easy for me to ruminate on the progress I haven’t made yet. It’s a rare moment when I step back and contemplate what I’ve accomplished over several months and think, “hey, good for you.” I’m trying to do that more often.

How do you think design will change in the next ten years?

Design will become more merciful as the design world becomes more diverse. The more perspectives, the more we might see ourselves reflected in the world.