Online Exclusive

Mapping Systems of Violence and Justice in Boston

By Augusta Meill, Executive Director, Agncy Design and Janelle Ridley, Director of Strategic Initiatives, City of Boston

During his most recent arrest, Marcus was taken by force and kept at the police station, sitting cold and hungry in the cell over the weekend. His court process extended over months, with multiple pre-trial appearances where he was supported by a lawyer he hired independently based on a recommendation from a friend.

Marcus ended up taking a plea deal and spent two years in prison. Now on probation, he is working construction and talking with his probation officer monthly. He describes his transition back to his life as “catch up” — facing the challenge of picking up where he left off while also wanting to be where his friends are.

Marcus’ story reflects the complexity of the justice system, and the many pathways that an individual may take while traveling within it. “The system” includes a range of city, county, and state agencies, as well as nonprofits and other stakeholders, each with its own set of motivations and approaches.

As the former District Coordinator for System Involved Youth at Boston Public Schools, Janelle Ridley has been enmeshed with the complexities of multi-systems that touch, hinder, and ensnare young people. However, despite her deep understanding of these systems from experiences throughout her career, explaining the intricacies of it all had proven to be a challenge, one that made it difficult to “lay it all out” in a navigable way. This laying out of the system is crucial to make those in power understand where changes can be made. For this work, Janelle partnered with Agncy Design, a nonprofit design firm, to use a system mapping approach, which has proven to be valuable, effective, and very much needed to start untangling the complexity of these intertwined systems.

At Agncy, we’ve been working with Janelle and the City of Boston to map “the system’s” many processes, stakeholders, and dynamics, with the goal of providing opportunities for greater transparency within these complex systems. Over the past two years, we’ve used system mapping as a tool for change and empowerment.

This approach has helped us understand what happens from the moment a young person gets arrested, to when they appear in court, and then to what happens after. It’s allowed us to weave a map of what happens in our city in response to a shooting, revealing itself as an interdependent web of stakeholders and highly conditional events. And, it has been a way to empower the users entrenched in these systems, helping them understand their own experiences and share their voices with those who have more direct power to enact change in this system.

We share here insights from this work—how we see these maps serving both system stakeholders and citizen users, and lessons learned as we seek to improve our own practice.

Mapping for Internal Alignment

System mapping is the process of understanding the people, dynamics, relationships, and protocols (both structured and organic) within a system, and representing these visually. This process can democratize information by making what is too often unspoken or implicit, a language spoken only by system insiders, accessible and navigable to a variety of people.

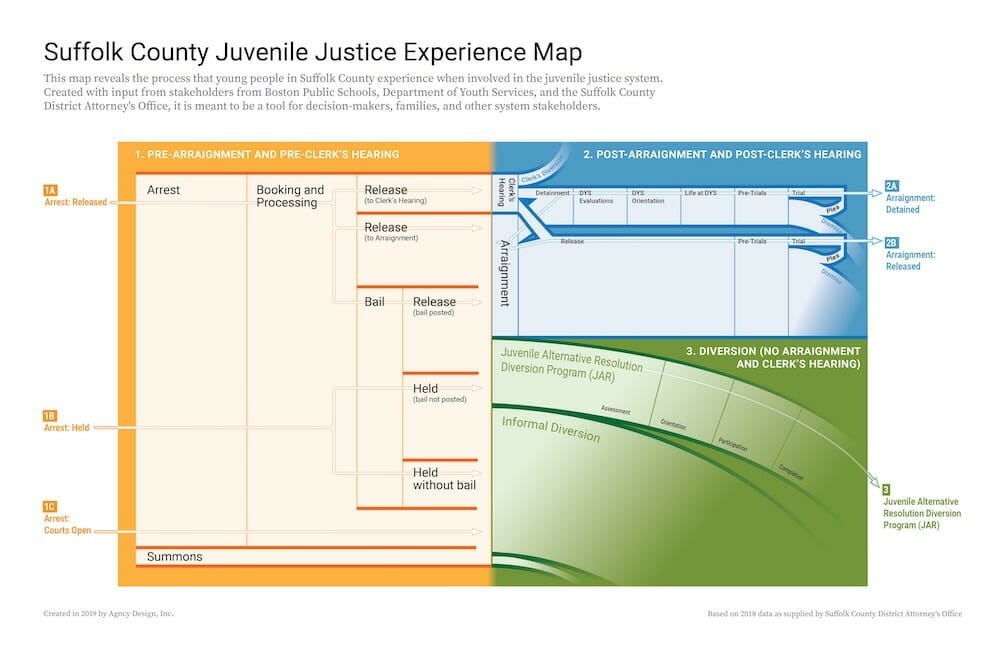

Our work mapping Boston’s Suffolk County juvenile justice system, from arrest to trial, is a good example of these system benefits. The maps we built help support stakeholders in making their work comprehensible. Systems are, of course, not static, but rather ever-changing collections of individuals who transition in and out of roles, taking their knowledge and relationships with them. System maps offer a clear articulation of the way things are done. Indeed, the maps we made for Suffolk County are now used by the District Attorney’s office as a training tool.

However, we see system mapping not as a tool for entrenching current practices, but as a vehicle for change. First, these maps align stakeholders from across the system, whether between different departments or different organizations. This alignment can bring people together to observe within the current state who is being served and how. It unlocks new opportunities, as a tool for identifying gaps or issues in the system and understanding how to harness current assets or dismantle existing structures to make these changes. In the case of juvenile justice mapping, these are being used in college coursework to educate the next generation of teachers, lawyers, or activists—folks who will be positioned to enact change.

The mapping process has confirmed for us the power of clarity in information, that simply getting the information down in a place that is accessible and shared has value. This need also reveals some of the core problems with the systems of justice that we are mapping.

Mapping to Cut Across System Languages

The process of mapping the justice system makes evident the lack of transparency within this system. We often find that information that is available to the public is scarce. A deeper dive into secondary learning reveals outdated data that is hard to decode. The best source of information has been interviews with system stakeholders, available to our design team only because of the access and relative power we have entering these dialogues.

These interviews reveal the different “languages” that stakeholders across a system speak. Each organization has its own internal vernacular and acronyms, reflecting the processes, perspectives, and values that it holds. Often these languages don’t align, creating an alphabet soup of steps, activities, or roles for users to navigate.

This interview-by-interview process of revealing the dynamics that make a system tick also exemplifies why system change is so difficult. It demonstrates how many people and organizations have to be bought into and protocolized into any changes. It highlights the reality that power is distributed unevenly across a system, and that incentives can be misaligned with what is right for organizations or stakeholders, at times in conflict with user needs or benefits.

Our work with the City of Boston’s Office of Public Safety to map the City’s response to a shooting is an example of a diverse set of organizations striving to coordinate across their landscape. The City’s strength is also its opportunity for improvement, as it has a slew of institutions that respond to a shooting incident to support victims, families, and communities. A shooting catalyzes movement from state and local agencies and organizations, and as all of these entities work together to support communities and individuals, they each bring their own priorities to the work. For example, while many focused on the needs of the shooting victim or their family, Talia Rivera, Director of SOAR Boston (Street Outreach, Advocacy and Response) emphasized her team’s work with the friends of the victim.

The SOAR team builds relationships with gang members to support them in finding paths as alternatives to violence. In SOAR’s work following a shooting, Rivera described her team’s ability to be chameleons, lingering with the friends of the victim to monitor, diffuse and serve as buffers, with the goal of preventing retaliation. The way that Rivera describes the multiple human sides of a violent event is an example of one stakeholder’s unique “language.” Other stakeholders in this shooting response map speak “languages” of community trauma, of individual support services, of prosecution. A map is a way to level language and put everyone on the same page.

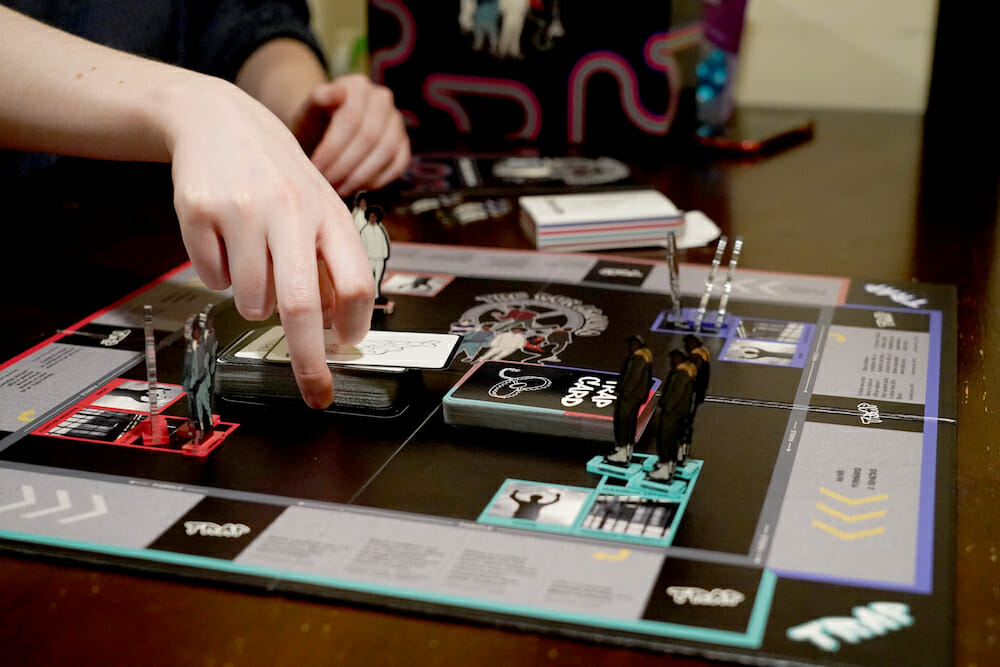

A young person plays “The Run Around” a game similar to Sorry!, where it’s almost impossible to win. This game models the system of incarceration and the difficulty of becoming truly free.

Mapping’s Power for Individual Users

The work that our team does to decode these different languages makes it clear the extent to which justice systems are not adequately accessible or just for citizen users. If the languages of the system are unclear to the stakeholders who do the work each day, working with citizen users reveals another layer of the experience, described through a personal journey, specific actions, and people. For example, in mapping the juvenile justice system with young people who had been involved in the system, it was evident how these young folks are put in situations to make decisions with little time, information, or support.

“I had maybe three minutes to make a decision [about a plea]: time to walk out of the courtroom and walk back in,” said one young person. “‘Do you want to risk it?’ That’s literally what the lawyer said. My sister and grandmother said, ‘Don’t risk it bro.’ It’s crazy how some of the judges make you pick right then and there, the judges that determine your life.”

Through our work we have also been able to reveal how different the perception is between citizen users and system stakeholders. While system stakeholders helped us fill pages of information on the process from arrest through trial, for the young people who had experienced this process, this was a side note compared to their experiences of arrest or incarceration. And yet, it was the part of the process during which they (in theory) had opportunity for influence.

A concrete example of the experience of the citizen users can be found in our work with iThrive Games Foundation and the SEED Institute on programs that use games and game design to equip young people with social and emotional skills. Through the work of game design, system-involved young people explore how their experiences with the justice system have impacted their mental health.

A board game that this team produced, called The Run Around, is an example of the user’s perspective of the system. This game is similar in play to Sorry!, with players moving from maximum security, to minimum security, to parole, and ultimately freedom. It’s been designed, however, to make it nearly impossible to “win” (become truly free), soon devolving into a sense of utter frustration and futility.

Its lead designer, a young adult who has been through arrest, trial, and incarceration, said of his experience, “Everytime I’d go [to court], I’m not myself. I would listen, but my mind is like, ‘Get out of here, go home.’ I wasn’t really in control in my life or myself when I was in court. I was moving, but I don’t know how I was moving.”

This response is typical of the young people Janelle works with. They often do not have the ability to process what is actually being asked of them, or have the support to assist them in making the best possible decisions. Their voice is not heard; a lawyer who is usually inundated with cases may spend very little time getting to know them as an individual and have only a few minutes themselves to decide how to go forward with the case. A powerful product of these aforementioned tools is making this reality both visible and visceral.

Systems are People, for Better or Worse

Our work with system stakeholders often highlights the deeply relational ways that current systems work. Nearly every person that we speak with tells us that their effectiveness is based on who they know and the trust they’ve built with those folks. While this is beautiful to see in action, it’s also fragile.

This relational way of working places much dependence on non-protocolized interactions. Functionality, too often, relies on folks going out of their way to make the right thing happen despite rather than because of the structures in place. Designers often focus on interactions, processes, or tools created with intention—the tangible and designed. But we find in our work that this invisible force of interpersonal connection is way more powerful, and often quite fragile.

There are many moments in the processes that we’ve mapped in which a single person’s decision twists the path of the user. A citizen’s experience of justice, their freedom, or their ability to receive services may rely on who they happen to encounter, that person’s response to them, and their ability to advise or connect them with others.

An example of this tension between system and individual can be seen in Janelle’s relationship with many system-involved young people. She demonstrates the importance of the individual in having a real impact on the lives of these youths.

She also brings to life the reality that much of this work isn’t supported by the system. It’s done through the will and love of the individual. There is nothing in Janelle’s job description, past or present, that creates the expectation that she will do this type of work. And yet, it is the work that is necessary.

Janelle is one of an as yet unmapped host of people doing this work informally or without explicit structure. In interviewing young people, we hear about the folks who show up for them, and we also hear about how fleeting this can be: they lose touch with a teacher when they leave school, or a mentor at a community organization moves away.

Mapping has helped us understand that a strong, equitable justice system needs to build from and to support these relationships. It must retain this humanity; the people we have interviewed are committed to serving the people they work with. They come to this challenging work with a desire to do right by their community. An equitable system also must be more resilient than any single person within it, with structures that are user-centered and designed to enable the best in people.

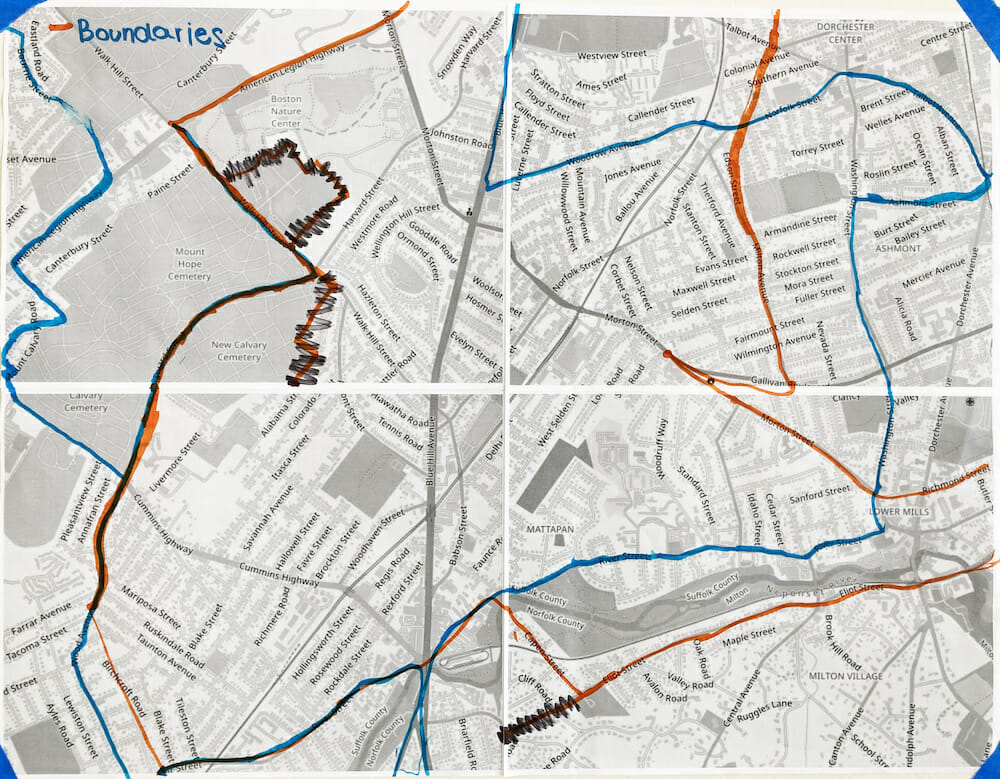

A map of two sets of boundaries of the same neighborhood – one defined by the City of Boston and one defined by a young person who lives there – created during the Transition HOPE program.

The Limitations of Our Work

Finally, we seek in our work to question the role of mapping, the types of data that maps represent, and the ways that they bring this data to life. While our mapping work seeks to capture perspectives across a system, reflecting a range of perspectives, types of expertise, and power, we’ve not yet developed a synthesized solution that brings these facets together. Hopefully this will be the next iteration of our work!

We also know that the design of our maps reflect a Western approach to map-making. Dominant mapping historically represents a colonial viewpoint, continued today by surveillance-based mapping and data collection. There is a rich history of mapping counter-stories—non-dominant maps that reflect alternative mental models and ways of framing data or building taxonomies. While we strive to explore these, we’ve not yet liberated our own models to stretch our design into these places.

The best way we’ve found to rethink these frameworks is by pushing the design work beyond ourselves. For example, we worked with Transition HOPE, a summer program for system-involved youth that provides programming at colleges and universities across Boston. The objective of the summer program is to hold high expectations for every young person, to provide opportunities that are realistic and within their perspective, to help the youth envision pathways to success by taking ownership of decisions for desired long-term outcomes, and to provide encouragement to help youth acknowledge that success is theirs to claim and define irrespective of the past. Transition HOPE offers youth seven weeks of project work with professors, giving them hands-on explorations of college and career pathways.

We spent one week with this cohort, working together to map various aspects of their spaces, communities, and relationships with violence and policing. Our process emphasized putting lived experience on the same level with more “formal” data, intentionally giving these two types of information equal importance. We explored various aspects of mapping (e.g. boundaries, locations) and overlaid different types of data, each time using the expertise of the young people and more typical system data such as police reporting.

Of course, we found that the young people had wisdom that the formal data didn’t reveal, and we also realized how much their perceptions of their communities were ingrained by systems of violence and policing.

For us, the take-away is that mapping must be simultaneously about the outcomes (the tool) and the process (the engagement). Actually doing the work can be as valuable as the tool itself in bringing people together, developing a shared understanding, and building capacity. The mapping process can be a mechanism for learning, self-reflection, and for shaping new solutions.