The Ghosts of Prisons Past

This is a horror story.

Illustration by Jon Key

By David Lamb

The kind of parable Ralph Ellison crafted in Invisible Man, which is to say, not a work of science fiction or fantasy, but of the phantasmagorical effects of systematic racism.

Like many writers I am haunted by ghosts. Many times, these ghouls are tangible: the specter of family trauma or glimmers of relationship drama. Sometimes, however, these phantoms are more elusive. They haunt me and I don’t even realize they are plaguing my thoughts; fighting to express themselves and forcing their way into dialogue, characters, and plots.

For many years, I was haunted by the ghost of the prison industrial complex, both as a result of my exposure as a potential victim and my experience as a potential enabler. This guilty presence forced its way into my novel, On Top of the World—a reimagining of the story of Ebenezer Scrooge in a modern hip hop context. Instead of old Scrooge fashioned as a Victorian money lender, he takes the shape of music’s biggest star and biggest sellout. Young, Black, and handsome, he is at one and the same time a potential victim of the relationship between prisons and profit—and through his thuggish, materialist messaging— one of its foremost enablers.

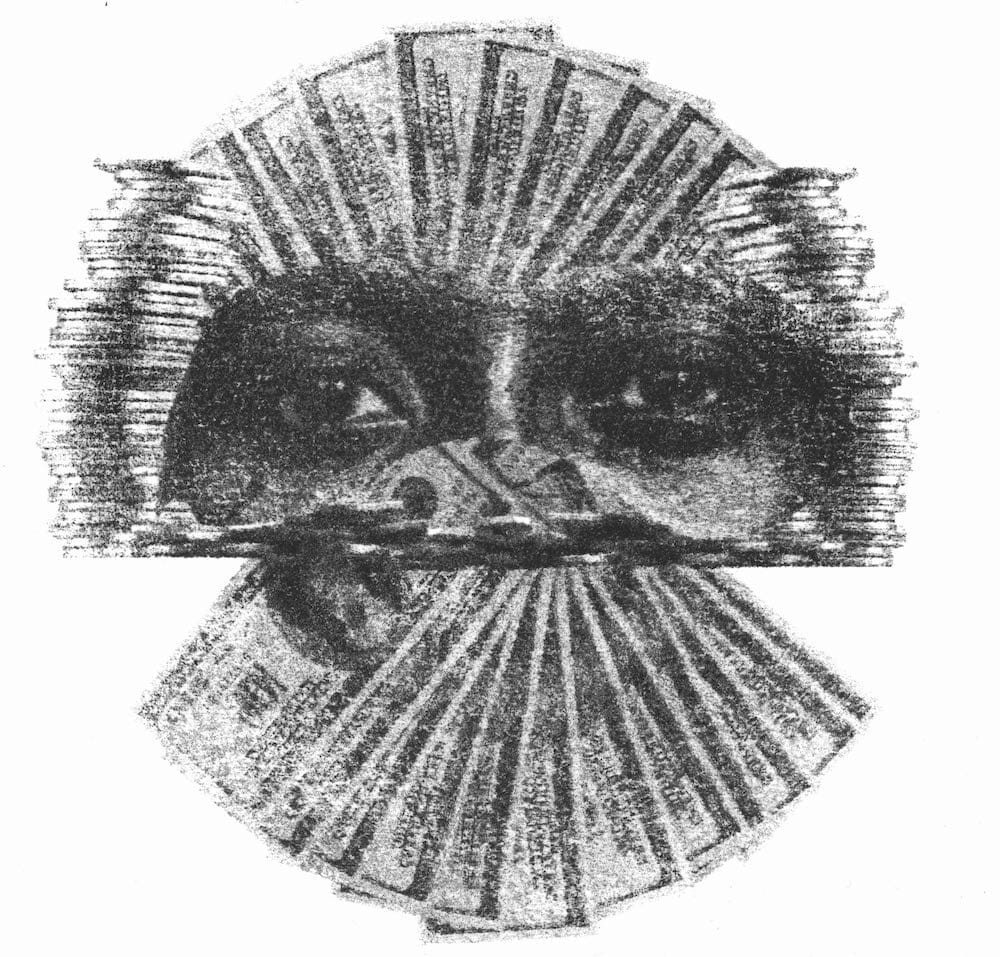

But where did this story come from? From the visions that haunted me. As writers we draw inspiration from our own lives for source material. And without truly realizing it, I was drawing from the horror I experienced when I connected the dots between what on the surface was the seemingly innocuous work I was doing as an attorney working as Bond Counsel on Wall Street in the early 90s and my witness of the concurrent terrors of the federal government’s War on Drugs. The sudden, shocking realization that these deals—worth tens to hundreds of millions of dollars for prisons, euphemistically branded “youth facilities”— were in fact part and parcel of the acceleration of mass incarceration for profit.

Plausible Deniability and the Unspoken Code

Let me begin before that realization, back to the last time I was nearly arrested by a system designed to incarcerate.

It was Thanksgiving, 1992. My cousin and I had gone to the movies. Afterward, we hailed a cab, but rather than driving us to our destination, the driver told us, “Black people have to pay first.” Rather than agree, I began writing down his license number to report a com-plaint, but he reached back and snatched his identification before I could, and then began driving off erratically before screeching to a stop just in time to avoid crashing into a police car. Two irate, young cops clad in white privilege and blue uniforms hopped out of the squad car demanding to know what was going on, but before I could utter a single syllable, they had immediately jumped to the cabbie’s side; threatening to arrest my cousin and me for “theft of services,” because the meter read that we owed $2.50. In a moment of outrage, I played my lawyer card, telling them the firm I worked for on Wall Street, and asserting that I wasn’t paying a thing. One young officer said, “Yeah, you sound like a lawyer, you’ve got a big mouth.” I replied, “Be that as it may, I’m not paying a thing.” They then asked us how we knew that the cabbie wanted us to pay in advance because we were Black. We replied, “Because he said so.” At which point the shocked cops asked the cabbie, “You said that?!” It seemed clear to my cousin and me that the officers’ response was not out of any sense of fairness. Rather, it was an admonishment for the cabbie’s frank honesty. We read their intention as a warning to him: “Don’t you understand how this works? Be racist, but with plausible deniability.”

Plausible deniability—that’s what public service rhetoric and platitudes such as “Courtesy, Professionalism and Respect” give law enforcement: a veil of plausible deniability that masks systematic racism. But whatever the platitudes, the system continues to work as it was designed, which was driven home to me when mere moments after giving us the cabbie’s license number those same officers trailed us in their squad car as my cousin and I walked to the train, all the while glaring at us and whispering racial epithets. The veneer of plausible deniability completely stripped away.

Bonds for Bondage

This brings me to the moment of the realization that I was unwittingly enabling this system whose endgame was mass incarceration to expand its reach. I had just graduated law school and was working on Wall Street as Bond Counsel. Bond Counsel—it sounds so innocuous. Unlike other lawyers, Bond Counsel does not technically represent a party. Instead, lawyers ostensibly represent the public good. You can think of it this way. Thanks to another lawyer, Ralph Nader, Americans now have greater consumer protection laws because a Bond Counsel negotiated a deal with the federal government on behalf of the people. Working on behalf of the public means that Bond Counsels are entrusted to represent an underlying social contract a government forms with its citizens. It acknowledges that, such as in the case of consumer protection, the people cannot rely on promises from manufacturers or experts hired by the manufacturer to work toward social good against their financial interests. Good luck driving that exploding car.

This was the situation that bondholders found themselves in during the 19th century, when rich railroad moguls would issue bonds for the construction of railways they had no intention of building. Bondholders, taxpayers, and cities were left screwed in the process. In order to protect the public and stop these types of fraud, the position of Bond Counsel was created to:

• Study the law related to the bond issuance

• Issue an opinion confirming that the bonds are indeed validly issued and have a legitimate purpose and source of payment

• Determine whether the bonds are tax exempt

These procedures are put into place and executed in order to professionalize the process, and, in theory, to protect people from fraud. But remember, this is a horror story, and beneath the veneer of respectability and professionalism that surrounds both the police and the bond market, there’s a monster that feeds on greed lying in wait. The terror is much worse, I discovered, when it’s not just a greedy corporate titan, but the governmental system itself that is engaged in morally decayed practices whose perpetuation and expansion rely on the sale of valid government bonds. Yes, the bonds may be legally issued and the bondholders can be assured of payment—but what is the source of payment, and even if legal, what if it’s immoral?

This is the question I was forced to ask myself when I realized that the “youth facilities” bonds I was helping to be issued were in fact paying for the construction of prisons that validated the capture and imprisonment of more Black bodies. In fact, the debt and interest on these bonds had to be paid by housing more and more prisoners in these facilities. Without enough prisoners, the bonds would default and the system would collapse; and so the secret truth was that in the land of the free there was simply not enough crime to justify the construction of so many prisons.

Take the state of Minnesota as a case in point. In 1992, through the use of $28.4 mil-lion in bonds, the state financed the construction of the Prairie View Correctional Facility. And like the old railroad bond catastrophes from a century before, it was a disaster. The shiny, new 1,600-bed prison opened to much fanfare—and then—sat empty. The project had been built to stem the economic decline in the city of Appleton, Minnesota—a tiny, overwhelmingly white, rural town of less than 2,000 people—by creating nearly 200 jobs. The prison was constructed, but there were no prisoners—the stage was set for a massive failure. But in this moment of need, the towns-folk leapt for joy when the city of Appleton signed a deal with the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico to house 516 prisoners. At the time, government officials were elated. Paul Michaelson, Executive Director of the Upper Minnesota Valley Regional Development Commission, concluded, “This project has had a positive effect on the whole region. It shows us that people want to stay in this area or move back here as long as there are jobs.” Articles even applauded the fact that some of the prospective prison staff had even begun to study Spanish to better communicate with the new inmates.1 More recently, Minnesota state representative Tim Miller (R-Prinsburg) submitted a new bill requesting that the Appleton prison be reopened, celebrating the “roughly 300 good-paying union jobs to Swift County residents” that would be created as a result.

And it wasn’t just Appleton. To solve this dilemma of not enough crime, other states began importing prisoners from Puerto Rico. Let me state that again—some states began importing prisoners from Puerto Rico, in order to have enough prisoners to justify their excessive prison construction and receive enough funding to pay the bond debt, which would come from the money the Puerto Rican government would pay them to house prisoners.

As an African-American who grew up very intimately with the Puerto Rican community in New York City, this was a horrifying, demoralizing discovery for me. I had to ask myself, “What if these prisoners were from Ghana, Nigeria, or Senegal?” Would I then have unwittingly been a participant in a mod-ern-day Triangular Trade reminiscent of the trade that brought untold enslaved Africans to the Americas in the hulls of ships? And if so, is the monstrous system continuing to operate the way it was designed not just for decades but centuries?

The system was intentionally designed to leverage the opacity of the bond issuance process. If you didn’t look too closely, you would see the movement of paper, data, funds, and resources from one place to another. At each stage in the process, the facilitators of this process could move their pieces at a purely procedural level. In abstraction, no one was actually exchanging money for human bodies, except that everyone was. The bond itself lies at the root of bondage; and the issuance of bonds to contribute to the movement of bodies from anywhere—New York, Puerto Rico, Ghana—into prison cells (or, remember that these were intentionally branded as “youth facilities”) finds a close equivalent to that Triangular Trade that constitutes the immoral center of our national, social debt.

Lest you think this is a problem of the past, let me note that the economic devastation caused by Hurricane Maria in 2018 spurred the Puerto Rican government to once again seek to ship prisoners to the mainland.

This pattern is reflected all over America, the need to house prisoners (from mostly poor, Black and Latino inner-city communities) to provide jobs and economic vitality for decaying, mostly white, poor rural towns. By design it fosters racism inherently when the only Black and brown people in your small town are in prison. By design it increases crime inherently, because you need more and more arrests to feed the system to pay the bonds—and therefore the definition of what is criminal by design must expand. Which is why, even though marijuana was “legalized” in Colorado, the law was designed in such a way that in Colorado, Black folks still get arrested at four times the rate of whites for marijuana possession.

The more I look at the picture, the clearer the dastardly design becomes—to pay the debt which enabled their excessive construction, prisons must have prisoners. The truth is, we don’t need so many prisons. The truth is, we can reduce crime with less police. The truth is, this is neither conjecture nor romantic fantasy, but it is rooted in the facts on the ground in Camden, New Jersey. Once regarded as the most dangerous city in America, Camden had to rethink policing after it was forced to lay off half its police force due to budget cuts. To adjust to these drastic cuts, Camden reimagined the architecture of its police force; shifting to a focus on community policing and improving relations between the police and the community, and guess what—crime went down. Between 2012 and 2019, the murder rate in Camden fell 63 percent. Yes, crime rates dropped across the country, but not nearly by that much. Police Chief Scott Thomson said that things began to change when he shifted the officers’ identity from warriors to guardians. There were still problems, such as massive overwriting of fines for petty offenses (a particularly egregious way that poor cities finance their budgets on the backs of poor residents), but after community complaints, the department moved away from this practice, relations with the community began to improve, and crime continued to fall.

The moral of the story is that not all horror stories have to end tragically, but it requires vision to write a new, more hopeful narrative.