Gliding to Success

The MBTA and thoughtbot Launch an App for Train Officials

The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA), known locally as simply “the T,” is the leading public transportation provider in the metro-Boston area. Before the majority of the city was restricted to the walkable radius around their homes, the MBTA and thoughtbot partnered for a digital communications project on the T’s most complex line, the Green Line. The Green Line is a light rail system, with multiple branches and a two branch extension currently underway.

Photo by Kyle Tran

By Jaclyn Perrone, Design Director, thoughtbot & Katrina Langer, Head of Web and Content, MBTA

Picture it: a trolley click-clacks through treelined streets, carrying baseball fans and college students down Commonwealth Ave in Boston. It stops at Harvard Ave, where more than 4,000 people board the train every single day. Passengers tap their CharlieCards and load cash on their tickets, asking the driver where to exit for Fenway, or where to transfer to the Red Line. Meanwhile, cars cross in front of the train–over 4 lanes of traffic and 2 sets of railroad tracks to continue their journey up Harvard Ave towards Downtown Boston. Then, the traffic light turns green, indicating that the train can cross the intersection, but a few people are still waiting to board. The operator holds, and by the time they’ve closed the doors and are ready to leave, the light is red. So they wait.

Meanwhile, the train behind it is just leaving Warren Street—it’s supposed to be 7 minutes away from Harvard Ave., but it’ll be there in 4 minutes at this pace. An official at Harvard Ave. radios the operator. “The headway gap is too short,” they say. “Wait at Warren Street just an extra minute.” At this point you might wonder, “Isn’t it a good thing to have trains arrive closer together, especially on a busy day when there’s a Red Sox game?” Well, not quite. In fact, maintaining even headways—the time between each train’s arrival—is essential to the efficient operation of the Green Line. Evenly spaced trains are safer, reduce crowding, and ensure there aren’t empty trains needlessly traveling through the system. The officials who make decisions about when trains can leave are called inspectors. During rush hour, there may be as many as 19 inspectors in the field deciding when to send new trains into service from the rail yard, assigning operators to trains and scheduling their breaks, monitoring crowding at stations, and yes, making sure trains are evenly spaced during service. They do all this over a radio station dedicated to Green Line operations, and with paper forms called train sheets. Radio communications and paper forms have served the Green Line well. As far as processes go, it’s easy to learn and keep consistent.

But in 2018, as the MBTA’s Customer Technology Department was wrapping up a significant re-build of the technology that powers real-time information for customers, they started to wonder: Could we use this technology to surface real-time train data for operations? They were pretty sure they could, but wanted to partner with a design firm that could bring leadership and rigor to the process—that’s where we came in. thoughtbot is a design and development consultancy that partners closely with clients to bring products from validation to success while mentoring them on the process. We kicked off a 3-month project with the MBTA team called Green Line Intelligent Decision Execution System (GLIDES). Discovery In the initial discovery phase, we learned a lot about Green Line operations. It’s about way more than just monitoring traffic lights. When the MBTA came to us, they had an objective that they wanted to solve: How might we improve communication between officials on the Green Line? The first phase of design thinking is Empathize, which means learning about your customers and the world in which they operate. In order to do this, we interviewed 21 MBTA officials, operators, and supervisors to get a better understanding of how the Green Line operates as a whole, across all the different positions. We had a series of objectives for our interviews:

• Get a sense of the different relationships within Green Line operations.

• Evaluate where we can supplement manual processes with technology.

• Identify inefficiencies and communication gaps in their workflow.

• Understand the broader context of Green Line operations.

• Identify at what points officials need more information to perform a task more efficiently.

• Identify user needs that are unarticulated. Focus on their feelings towards a particular workflow and their motivations in certain situations.

thoughtbot and the MBTA team held one-on-one, hour-long interviews with different officials over the course of a month. Oftentimes, our team would split up and interview multiple people in one day to cover more ground quickly. We asked questions such as:

• Walk us through your typical day.

• What’s frustrating?

• What’s rewarding?

• What types of decisions do you make throughout the day?

• What types of information do you need to be successful?

• What is challenging to access?

• Can you tell me about a challenging experience you had on the job?

• How did you handle it?

• What tools did you use?

• If you had a magic wand and could fix one thing right now, what would you fix?

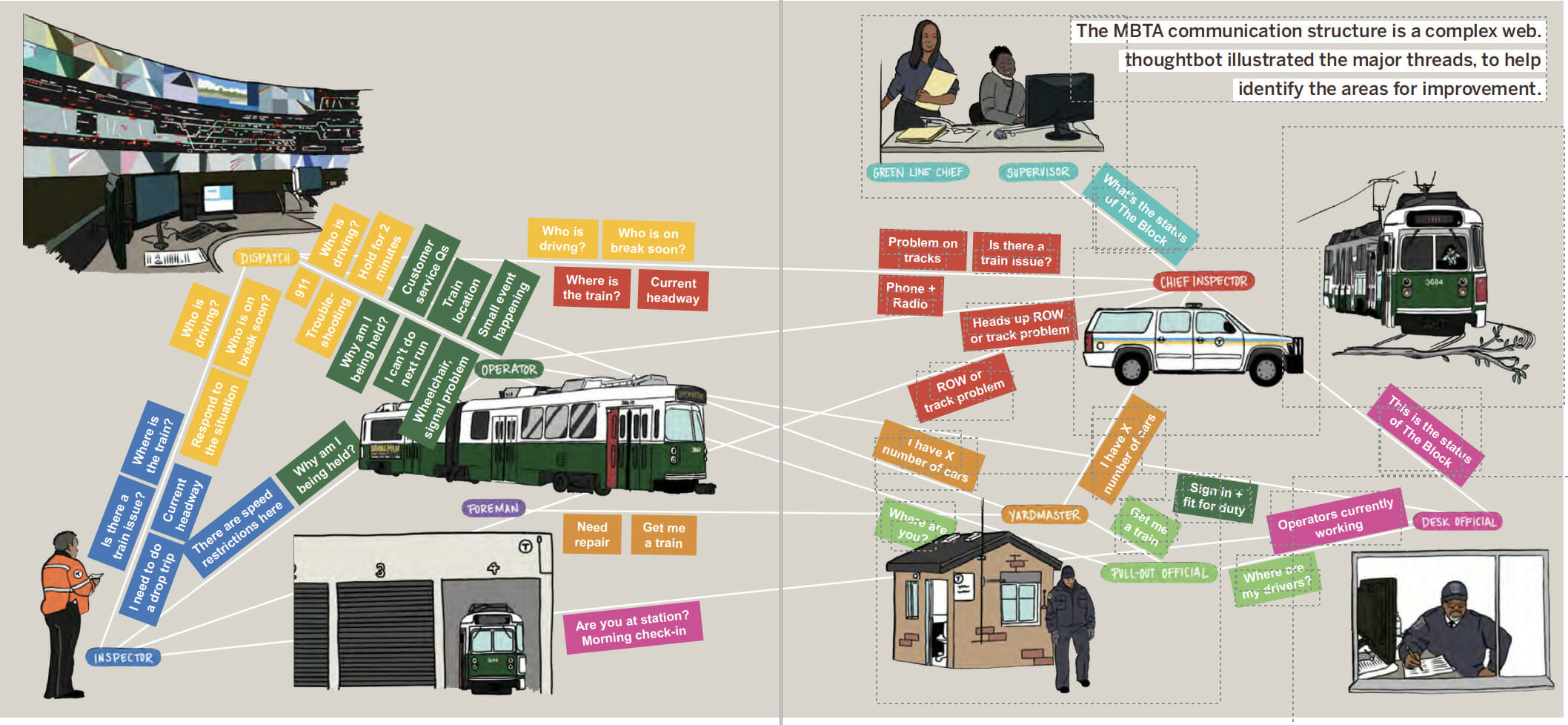

After a day’s interviews were over, we would come together as a team and synthesize. We captured our observations (things we heard, saw, felt) on sticky notes, and over time clustered similar ones together to form overarching in-sights. We came up with over 30 insights, all of which could easily spin off into their own product offering. The task at hand was prioritizing these insights and choosing one that we could tackle together in this short time that would yield the highest impact. This marked the second phase of the Design Thinking approach: Define. Now it was up to us to use these insights to determine an objective to work toward that focuses on a critical, common, unmet need that we heard throughout our interviews. In order to inform the priority of our ideas, we created a series of user personas to further document our findings. We aggregated our findings into seven different personas, featuring the Chief Inspector, Desk Official, Dispatcher, Operator, Pull-out Inspector, Supervisor, and Yard Master. The personas dove into topics such as: Goals, Behaviors & Habits, Technology Access, and Relationships. It was important to create and share artifacts like these from the research phase to help inform future MBTA projects. Once we established an understanding of the different players in the Green Line ecosystem, and the nature of their relationships—including the questions they asked each other and the blockers they experienced—we revisited our insights and determined that reducing radio chatter would have the greatest impact on their community.

At this time, Green Line operations used a single radio channel for communication in order to ensure that all operators and inspectors were kept informed of critical service information. However, there were times it was taken up with questions that could be easily answered through software (e.g. Who is operating a particular train?). Questions like these prevented more urgent information from being distributed, which introduced challenges into the communications flow. For the Green Line, timing is another logistical challenge. For example, operators have scheduled, paid breaks during their shift. If the train they’re driving gets stuck in traffic on Huntington Ave., it delays that break time. They’re still entitled to their full break, but then the next train they’re scheduled to drive will need to leave later. Furthermore, while inspectors can see where trains are scheduled to be according to paper train sheets, real-time information about train operators and locations was only available by radio. This makes it difficult to adjust train schedules according to breaks and shift changes.

Finally, inspectors can (and do) use Green Line radio to find out where the trains are and who’s driving them. As a result, the radio channel is full of chatter-communications about break times being delivered right alongside in-formation about emergencies.

Prototype

After developing a problem statement (How might we reduce radio chatter?), we were now ready to begin the third phase of the Design Thinking approach: Ideate. As a team, thought-bot and the MBTA sat down and did a series of design exercises to help us generate as many solutions as possible to solve our objective. We started with a round of Mind Mapping, which is used as a warm-up exercise to get our ideas out of our heads and onto paper. From there we did a few rounds of a rapid sketching exercise called Crazy Eights, to get as many solutions and ideas out as quickly as we can. Finally, we finished up with an activity called Story Boarding, which allowed each of us to develop an idea further by diving into the details of its interaction. After a few rounds of sharing and critiquing our ideas, we converged on a final storyboard that outlined the screens of the prototype we wanted to build.

Our research revealed a number of opportunities for improvement, so we continued our process by building an app prototype that mirrored paper train sheets. Accessible via any browser on smartphones, it includes train location, operator information (the badge number and scheduled shifts for two people on each train), arrival predictions, and a visualization of headway gaps. This took us right into the last two phases of the Design Thinking approach: Prototyping and Testing. Our first prototype had a few key objectives:

• Provide more context about what’s currently happening in the system.

• Create a way for Green Line officials to keep each other updated about non-emergency issues.

• Improve the fidelity of our data by making crucial train sheet data digital.

These objectives took the shape of an experience that showed train location, operator information, reported issues, and train sheets. We created this experience as a low-fidelity, click-able prototype to start, so we could get it in the hands of officials quickly to hear their feedback and iterate on the design. This prototype wasn’t functional—it was a series of static screens created in a design program called Sketch, and linked together in a prototyping tool called In-Vision. We went back out to our interviewees and showed them the prototype on our phones to get their feedback. We asked questions like “What’s happening on this screen? What information is missing here? When would you use this feature? What would you do next?” After multiple rounds of showing and iterating on our prototype, we started to have a clearer idea of what we wanted to build for our first version of the product, our MVP. thoughtbot and the MBTA created a backlog of all the features that we wanted to include in our first build, based on user feedback from testing. Once this list was created, we prioritized and honed in on which features would be required in order for our app to function and provide value. These features included train lo-cations, train sheets (entering who is operating which car), and a way to collect user feedback. We also decided to integrate analytics from the start in order to gather information on usage to inform future iterations. With a plan in place, we started designing and developing the first version of the app. Designers honed in on visual styling and user experience, while developers laid the foundation for the back-end functionality. After a few weeks, we had a real, working app! It was piloted by 7 inspectors on the B and C branches of the Green Line. We wanted to learn three critical things. Was the app easy to use or were there barriers to access? Did inspectors think it would help them do other parts of their job? Was this a scalable process, ideal for us across all parts of the Green Line?

Expanded Pilot

Once thoughtbot and the MBTA understood that the app was useful based on our prototype, we expanded the pilot to inspectors at Reservoir, Riverside, Harvard Ave., and Boston College stations. This part of the test was about efficacy—or, does this app do what we think it will? In particular, we hypothesized it could even out headway gaps the way previous research suggested it might (reducing customer wait time by as much as 30 seconds). We also hoped it would provide more holistic, real-time information to inspectors and dispatchers on the Green Line, thereby reducing chatter on the radio, and helping everyone make better deci-sions about service needs along each line.

Results

In the first few weeks of widespread use, the team uncovered that this app provided a more equitable, reliable source of information for inspectors and dispatchers, and it did improve overall employee morale. And, while it didn’t measurably reduce radio chatter, it did ensure a consistent source of train and operator location information if the radio was needed to communicate disruptions or emergencies. Anecdotally, inspectors looked forward to us-ing the app every day. They loved the automatic updates to train location. Here’s the unfortunate news: About two weeks into our pilot last year, we ran into an issue with the GPS system. Essentially, unrelated to any of our work, the GPS service provider had switched network protocols, making location tracking unreliable (If you took the Green Line at this time and relied on arrival predictions through the MBTA website, Google Maps, or Transit App, you may have noticed this).

Over the next few months, all-new GPS units were installed on every Green Line train to accommodate the new GPS protocol. It wrinkled our hopes and dreams for the GLIDES app, but it did not deter our spirited approach: as of this writing, GLIDES is back up and running, to the relief of designers, developers, and Green Line inspectors, who, at least once a week while the app was down, emailed our team to say, “Hey, when is this app going to work again? We miss it!” Well, it’s back now. The GLIDES app is now in use, creating data to help the MBTA improve communications among train officials and to deliver a more reliable service to customers. And although our work on the GLIDES project is over, we’re excited to see how our partners at the Customer Technology Department will continue to build on the product development methods that we introduced and the research findings that we uncovered during our time working with them on the Green Line.