Through the Eyes of an Architect

An Interview with Phil Freelon

Three years after opening, tickets to the Smithsonian Institute National Museum of African American History and Culture are still almost impossible to reserve.

Photo courtesy of NC State University

Interviewed by Amanda Hawkins, Edited by Eva Hill and Susan Janowsky

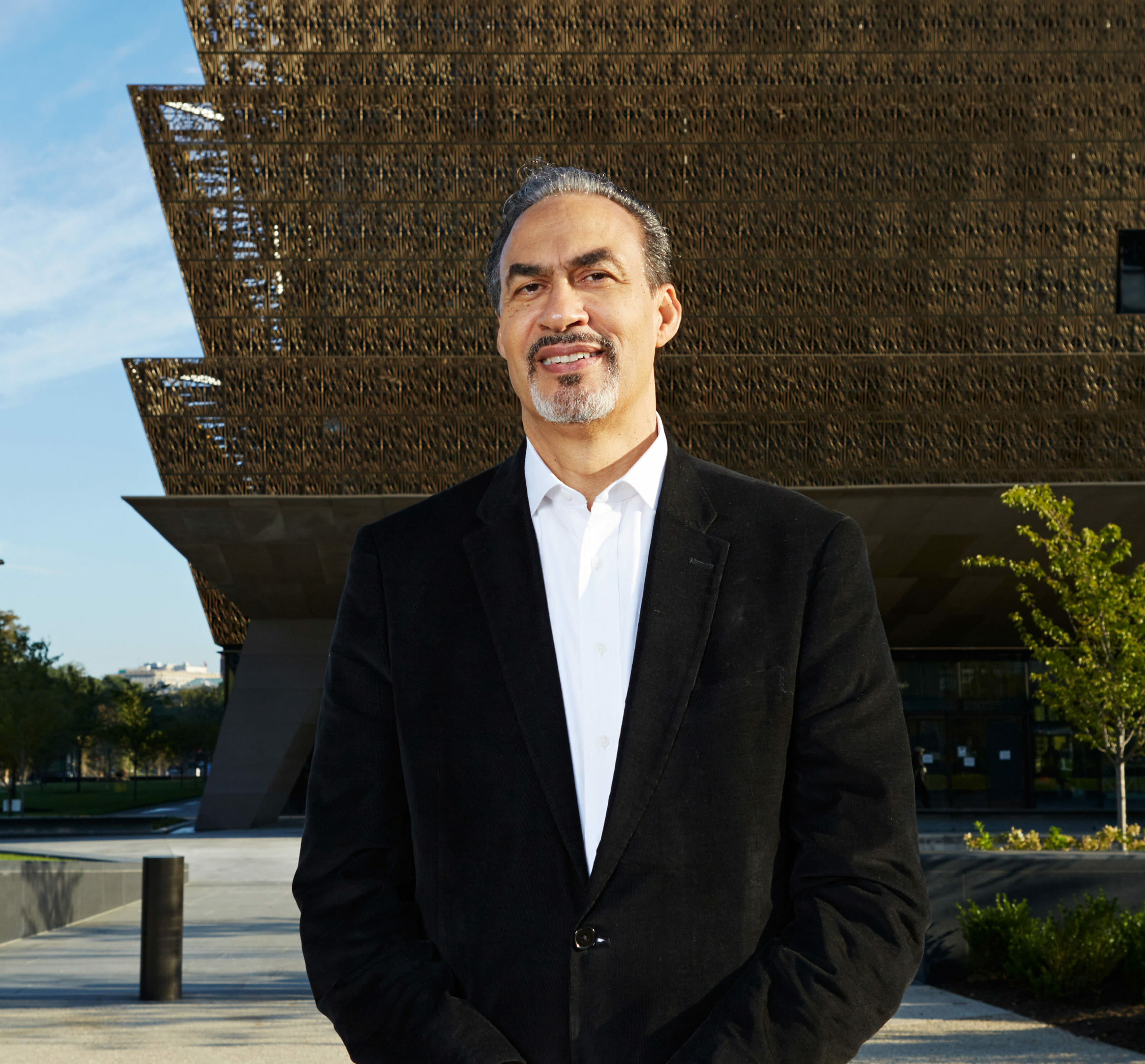

Phil Freelon was the lead designer of the newest Smithsonian Institute, and was also the Design Director of the North Carolina practice of Perkins and Will. He was an advocate for inclusion on both sides of design, the designers and the end-users, and always strived to provide beautiful public spaces that anyone can access. Phil at his core, was an architect.

Phil was diagnosed with ALS in 2016, and passed away in July of 2019 at the age of 66. In November 2018, Amanda Hawkins, Exhibitions Manager for CoDesign Foundation, spoke with Phil about his achievements and career path, as well as what he’d learned about diversity and inclusion over the years he’d spent working in architecture.

Photo by Noah Willman

Phil’s portfolio includes the Museum of the African Diaspora in San Francisco, Historic Emancipation Park in Houston, multiple library projects for the D.C. Public Library System, and the Durham County Human Services Complex. He was considered the leading designer of African American museums and designed both the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta, Georgia and the Smithsonian Institute National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. In 2011, he was appointed by former U.S. President Barack Obama to the National Commission of Fine Arts. Alongside his significant achievements in architecture, Phil was also an educator who taught professional practice courses at various universities, an avid photographer, and the co-founder of the Phil Freelon Fellowship at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, which offers financial assistance for students of color.

Amanda Hawkins: Could you tell me a little about growing up in Philadelphia?

Phil Freelon: My family was very much into education and the arts, so I had great exposure to museums and music, theater, and literature. My mother was an English major and taught elementary school. My father was a sales executive for a national company. My grandfather, Allan Freelon Sr., was a painter in the Harlem Renaissance. From a young age I would enjoy drawing and sketching and sculpting and painting, and I was encouraged by my parents because they saw interest and some talent there. Architecture seemed to be a really nice combination of the things I was interested in: the drawing, the three dimensionality of it, the creativity, but also the technical side.

There are only 100 accredited schools of architecture in North America. I was accepted to Penn State University and Hampton University, the two places I’d applied to. I knew something about Hampton because people from my church had attended. And it was a historically black accredited architecture school. In the late 60s and early 70s, I was interested in getting back into the Black experience because the high school I went to was mostly white. It was fine, I did well there, but I wanted to be around the Black experience, and [Hampton] was a good school with an architecture program. I accepted the offer to go there and had a great couple years there. One of my mentors, John Spencer, head of the department of architecture, he advised me to move on, which was a generous thing to do, to help his best student move on and up academically. He advised me to check out NC State and UVA, and so that’s what I did.

I was invited to come down to Raleigh to meet with the dean at NC State by virtue of Mr. Spencer’s connections. I was a little apprehensive about going further south as a Philadelphia boy; it seemed like the Deep South to me, but I found the people were friendly. It was a different era back then. It seems to me that the majority of institutions were seeking out African Americans; they were proud to bring people in. Nowadays there’s a stigma attached to affirmative action when that happens. Back then, it was exciting that there was a black guy coming to NC State when there weren’t many there.

I did very well there, I received the top design award in architecture when I graduated. And I went on to MIT for my master’s degree. My time in Raleigh made an impression on me; I liked the area and it seemed like I was poised for growth and one of my professors introduced me to a firm in Durham where he was a design consultant. So in the summers of ‘74 and ‘75, I worked in Durham and established some relationships that later in my career, after grad school, I followed up on.

Curious about other leaders in creative careers? Want to learn more about race, gender, sexual orientation, and more intersecting with design? Visit We Design: People. Practice. Progress.

AH: While you were at NC State, were you trying to make an impact with your design? What were your goals?

PF: Not yet, I think. I was just trying to absorb all that I could. At that stage you don’t know enough to be able to pick a career path that’s specific within architecture. I didn’t start my firm until 14 years after MIT. It’s quite a career path, just getting certified and licensed and gaining enough experience to the point where the client will say, I trust you with this multimillion dollar building I want designed. People want to know that you’ve done it before and that you have some kind of track record.

When I started the Freelon Group, I wrote a business plan and I had a vision and a mission and that had to do with doing certain types of buildings and not doing other types of buildings. It’s helpful to have some guiding principles so I could explain to people who might want to work with me, this is what we’ll do together, and this is what we won’t do. For me, that was working on schools, higher education projects, cultural centers, community centers, museums and libraries, and having a clear vision of not doing things like prisons, shopping centers, or casinos. If it doesn’t have a positive impact on the community, I wasn’t interested in building it. I learned early on if you say yes to the wrong things, when the right things come along you may not be at the capacity or able to do it. We’ve been able to stick to principles established early on that have served us well.

AH: What else motivated you to work on cultural and civic projects?

PF: I was drawn to the projects that I could feel proud of after I was done. A lot of those happened to be in the public sector, they weren’t corporate headquarters and things like that. I’d be happy to do those, but not as my main focus. The other reason that the public sector has been good for us is the clients. They’re often a school board or city council or governor or mayor and the people that work in those environments tend to be rather diverse so we were able to distinguish our firm just by virtue of how we looked. One might say, well, being a black architect when 2% of all licensed architects in the country are African American, that’s tough. Well, I say that’s the distinction that we bring in a homogeneous profession. I’m just an optimist – I’m a glass half full kind of guy. I always thought that we could compete with mainstream firms because I was able to compete at NC State and MIT and I knew I was as good as any of the folks in these places.

AH: Having diversity of your staff worked to your benefit in this sector. Were there any challenges that having a diverse team presented?

PF: Yes, I mean, architecture being dominated by males, there’s the good-old-boys system, to use a cliché, and I’m not part of that, so that’s been a challenge, but complaining about it is not productive, and so you just do the best you can and compete hard, and I’ve always felt that people will not let prejudice get in the way of business decisions or they won’t be in business very long. So while it’s true that there’s discrimination and inequity across the board in this country, if I thought that was going to stop me at every instance I wouldn’t have gone into this profession. I believe that clients – governments, school systems, whoever the client may be – will recognize excellence and talent in a business environment, even if personally they may have some misgivings or hold certain stereotypes. Folks won’t let that get in the way of good business, because people that think the other way don’t get very far, and that belief has kept me motivated. I take pleasure in bursting the stereotypical bubble.

AH: Can you tell me more about the merger with Perkins and Will?

PF: One of the issues we’d been running into in recent years was that we were kind of in a no-man’s- land of size, where we were 60 people, which around here is considered a large firm, but on an international basis it’s considered a small firm, so we were kind of in-between, sizewise. We were doing work all over the country, so we weren’t really able to compete locally with the smaller firms. Clients felt like we were more focused on a national market. But then competing nationally, against firms like Perkins and Will, which is 2500 people, we found it hard to compete in that middle ground.

The other aspect of our practice that was challenging was that in cities that we were working in, we partnered with a local firm, which is not unusual. That was risky because you really don’t know what it’s like to work in partnership with another firm until you’re in it, and in each case, we’d try to figure that out ahead of time, but sometimes it was hit or miss. Perkins and Will had an office in every major city in the U.S. except for Philadelphia, so it was like having a built-in partner that you already knew shared the same values and principles. It’s unusual for a big firm, but Perkins and Will is one of the few large firms that values design and puts it first and foremost. So that was attractive to us, to say, if we’re doing work in Austin or we’re doing work in Seattle or something, we don’t have to set out who would be the perfect partner, we have built-in partners all over the country and internationally – they have offices in Sao Paulo, London, Shanghai, Dubai – and so that was attractive.

The third thing was that Perkins and Will actually had expertise in an area that we were dabbling in, that we weren’t able to show a strong portfolio for, and that’s healthcare. We had expertise that Perkins and Will was thin 16 on (that would be the museums, libraries, and cultural-focused projects). I became the design director and managing director of the firm’s Charlotte studio and its Morrisville office, which moved into my studio in Durham under my leadership. So it was a good situation for them and for me, and for my leadership crew, who are now shareholders. All the principals in my firm were made principals at Perkins and Will. It was one of my stipulations, and now they have opportunities, national and international, that I couldn’t give them at the Freelon Group. It was a great relationship and merger.

AH: What has been the most fulfilling thing for you since then, and how has your role changed?

PF: I assumed some firm wide responsibilities coming in through Perkins and Will. I’m on the board of directors for the entire firm, so that was a new and exciting and challenging role for me. The board meets quarterly in a different Perkins and Will studio, so I’ve been getting around the country and meeting new colleagues and peers, and participating in firm-wide decisions, both domestically and internationally.

I also serve on the research board. Perkins and Will has a research staff of about 20 individuals who are doing a number of different initiatives that feed into the design work that we do, so that’s been a new and exciting role for me. I’m also on the design board, which is separate from the overall board. There are a number of responsibilities, including internal design reviews of all the offices. We conduct a survey of every office’s design work throughout the year, and we get together in January and it’s almost like a design report card, office by office. We give feedback, and if we see that there are struggles or issues or challenges, we can offer guidance from a corporate level. We also sponsor an internal design competition where younger people from around the firm worldwide get to participate in a hypothetical design problem, and then it’s juried by outside professionals.

There’s a number of things associated with the design board that are focused on making sure that Perkins and Will remains at the forefront of design excellence. There’s also a peer-review process that we have, where a handful of us from the design board might visit a studio for a couple days during critical stages of design to help give guidance and feedback from the most experienced and accomplished designers in the firm, and I’m part of that. I’ve been to design review sessions to offer that kind of high-level guidance for important design projects that are just starting.

AH: What has it been like to bring education and mentorship into your work inside and outside the office?

PF: The architecture profession is not very diverse: about 2% of licensed architects in this country are African American, and that hasn’t changed in the past 30 or 40 years since I was in school, so it’s been a challenge and a concern of mine, and of the entire profession. This issue is not going to be solved or addressed by just waiting for something to happen, so it takes initiative and taking steps to increase awareness. My feeling is that if more young people were exposed to architecture and knew about it, then they’d be more inclined to pursue it as a career, so with that in mind I try very hard to make what I do visible beyond just the architectural community.

I’ve also, with Perkins and Will, sponsored the Phil Freelon Fellowship at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, which is targeted toward students of color who may need financial assistance. Because it’s not just about awareness, even once you get into school: staying there and excelling and being able to afford highlevel education is important as well. I’ve been teaching off and on in the university setting, first at NC State, then at MIT. For the past decade I’ve been teaching a professional practice course, and in doing so, mentoring students that we see coming though at the graduate level.

Photo by Katina Parker

AH: These days, how do you spend your time outside of work?

PF: I enjoy photography. To me, it’s an extension of the design work that I do. In photography you start with everything, you look around and there are millions of choices about what you see and how you want to record it photographically, so it’s working backwards from everything and choosing something very narrow, a slice of time, a moment, and a view, a perspective that only you bring – what does your mind’s eye see? – and capturing that.

For me, it’s kind of architecture in reverse, making choices about how you interpret the environment and what you want to share about that in a photographic image. The other thing about photography, for me, is that it’s something I can do by myself. It’s a solitary activity, it’s quiet, it’s a way to retreat into something else that’s related design-wise, because there’s composition and beauty and life and shadow, and the subjects I choose are primarily architecture and landscapes.

AH: What do you love the most about your career in architecture?

PF: I would just say that working in the public realm has been very satisfying to me. Doing so, I feel like we’ve been able to provide beautiful public spaces that anybody can access, so there’s not this exclusive thing where architects get these huge budgets to do these fancy museums or residences or corporate headquarters, and who gets to go there? Only the privileged.

One of the drivers in my career has been providing beauty and inspiring architecture for anybody. The bus station we did in Durham is a beautiful place, and the average person wouldn’t think that it’d be worth that kind of effort, but every day people go there and can enjoy an architectural experience. It may be not at the top of their mind, but they know it’s a pleasant place to be. So that has been a driver for me: what can I do, what can our firm do, to bring design excellence to everybody, not just a privileged few who can afford to hire architects and build monuments to their ego? I’d rather do something that everyone can enjoy.

Read more about Phil’s legacy here.

From Design Museum Magazine Issue 013

The National Museum of African American History and Culture

Freelon was the lead architect of a four-firm team known as Freelon Adjaye Bond / SmithGroup JJR that designed the NMAAHC. The team won the contract for the museum in 2009, and the building was completed in 2016. The structure incorporates elements of black history from Africa and the Americas: the building’s three-tiered corona references crowns in Yoruba art from West Africa and the exterior bronze lattice evokes ironwork created by enslaved African Americans in the southern U.S. The museum’s entrance is a welcoming porch, a feature found across Africa, the Caribbean, and the U.S. South.

Motown Museum Expansion

Freelon led the concept design for the

$50 million expansion of Detroit’s Motown Museum. The original museum is located in the Motown record label’s studio and in the building’s second-floor apartment, which belonged to the label’s founder, Berry Gordy. The expanded museum will feature interactive exhibits and a performance theater, and is expected to bring increased tourism and economic stability to the surrounding community. This project is still in progress.

Emancipation Park

Emancipation Park, established in

1872 in Houston, Texas is located in the historic center of the African American community in Houston. The park hosts Juneteenth celebrations every year, and was first purchased to become a park by four people who were enslaved. The new design celebrates the park’s founders and commemorates Juneteenth with

a ceremonial gateway and promenade, and also features a recreation center, swimming pool, ball fields, theater, event lawn, and multiple covered picnic areas.

Special thanks to Perkins and Will for their support on this article.